Electric fence maker has positive news for gill health conference

Harbor offers hope for tackling jellyfish blooms at fish farms

A potential solution to the harm that stinging jellyfish can cause to farmed salmon in marine pens will be presented to the Gill Health Initiative forum that takes place at the Atlantic Technological University in Galway, Ireland, tomorrow and Thursday.

Innovative company Harbor and research institute Nofima, both from Norway, have together found a method that appears to neutralise both the “barbed wire” jellyfish Apolemia uvaria, stinging jellyfish and other poisonous cnidarians in the sea in a few seconds: electric shocks.

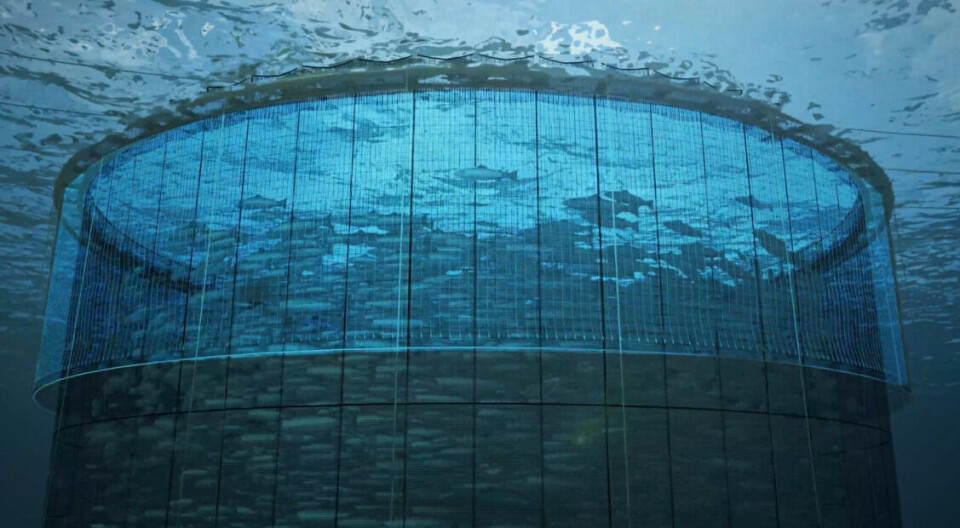

Harbor produces an electric fence for fish pens that uses low-voltage electrical pulses to inactivate sea lice before they attach to salmon. Work in the laboratory shows the fence may also be used to trigger jellyfish “nettle” stings before the current pushes them into pens.

The jellyfish must spend a long time rebuilding its venom reserves after releasing it. This means the jellyfish is considered harmless.

In a lab in Norway, Nofima researcher Bjørn Roth demonstrates the effectiveness of pulses by extending his arm. The skin on his forearm is light and normal – despite the fact that it has just been covered by a type of stinging jellyfish. No pain, no burning. No sign of the itchy, red rash that is usually associated with close contact with the jellyfish.

“Nettle cells sting or burn when they come into contact with skin. This stinging jellyfish has been treated with electricity and is now harmless,” says Roth.

The goal of the research project was to assess whether electric current can trigger the venom cells in jellyfish. And it can.

After experiments on blue and red (Lion’s mane) jellyfish and the barbed wire jellyfish, Roth and Harbor are confident in their case.

Not much venom left

“The results show that all types of stinging cells in jellyfish were released. There is not much venom left in these cnidarians. We therefore conclude that electric barriers – a kind of electric fence around the cage in the sea – can be an effective measure against cnidarians,” says Roth.

He has worked closely with Harbor’s biology manager, Tarald Kleppe, to test the Harbor Fence against jellyfish.

After just five seconds of exposure to electric current, the treatment is sufficient to render the jellyfish harmless.

“In the short term, an electric fence that ‘taxes’ jellyfish could reduce mortality in vulnerable locations. In the long term, electric fences will be used to prevent damage from jellyfish in general,” says Roth.

The work done so far was a preliminary study funded by FHF, the Norwegian Fisheries and Aquaculture Industry’s research funding body. Nofima and Harbor now hope to get funding for a further so that these positive results can be tested on a larger scale in the sea in collaboration with the aquaculture industry.