Scottish seaweed project may offer fish farmers a chance to cut carbon footprint

Researchers look at locally-grown algae as protein source to replace imported soy and fishmeal

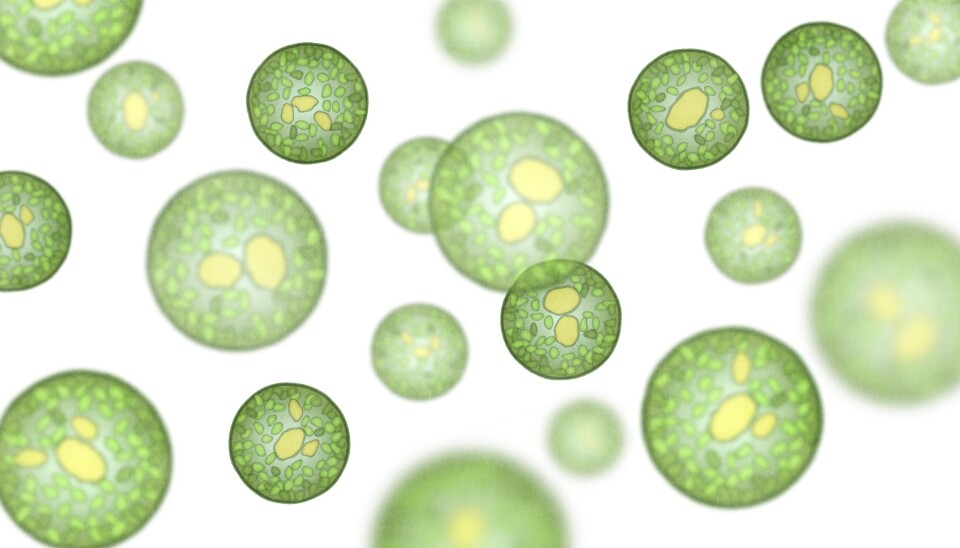

A new approach to growing algae (seaweed) in Scotland may offer a sustainability bonus for the aquaculture and agriculture sectors, by providing locally sourced, alternative protein sources and ingredients for feeds.

Experts in animal nutrition from BioSimetrics and Abrimar, both based in Edinburgh, are working alongside researchers at the Scottish Association of Marine Science (SAMS) to explore the optimum conditions required for growing algae as a novel feed ingredient. Funded by the Industrial Biotechnology Innovation Centre (IBioIC), the results of the project could help to unlock new Scottish supply chains for natural and sustainable feeds.

Previous studies have demonstrated the potential of algae as a high-quality, nutritious alternative to imported soy and fishmeal protein, however, the cost and complexity of scaling up to mass production has meant the process has not yet been developed further. For this project, species were specifically selected for their commercial viability, to minimise potential waste and maximise value, IBioIC said in a press release.

Multiple sectors

By taking a collaborative approach to growing and harvesting, the consortium has devised a new strategy where multiple sectors will use different components of the algae crop for different purposes. While some elements of algae would go into fish and livestock feeds, other co-products – which may previously have been deemed waste – could be used as pigments for a range of food and drink or consumer products.

The researchers have tested a range of organisms supplied by the Culture Collection of Algae and Protozoa (CCAP) at Dunstaffnage, Oban, to determine which species could unlock the greatest feed value for monogastric animals, fish and humans by measuring their speed of growth, protein yield and digestibility. The CCAP is Europe’s largest collection of living strains from freshwater and marine environments and has been created by SAMS.

Algae has a similar nutritional profile to soy, eggs, fishmeal and other commonly used protein sources. However, whilst algae can be grown locally, the UK imports around 3.5 million tonnes of soybean equivalents per year mostly from South America, with approximately three-quarters used for livestock and fish feed.

Abrimar’s mission is to identify and optimise the industrial cultivation and production of microalgae, macroalgae protists and black soldier fly larvae as an economically viable, nutritious, and sustainable high protein food source.

It wants to offer a digestible alternative to animal protein in animal and aquafeed formulations and to enhance the fortification of human food with essential protein, fats, and minerals.

BioSimetrics focuses on ruminants and uses in vitro gas production techniques (IVGPT) to measure the rate and extent of carbohydrate and protein degradation in the rumen, enabling a more precise formulation of diets and accurate predictions of feed intake and animal performance.

We need to optimise the process so that it makes sense economically ... we’re keen to find partners from other adjacent sectors to work with and explore the collaborative opportunity where we each get what we need from different parts of the plant and make the entire process more circular.

Dr Virgilio Ambriz-Vilchis, head of technical services at BioSimetrics

Dr Virgilio Ambriz-Vilchis, head of technical services at BioSimetrics, said: “Different species of algae have already shown huge potential in terms of the nutritional benefits for aquaculture and agriculture. However, transferring the process from the lab to full-scale production is not as straightforward as it may seem. As well as the technical hurdles, we also need to optimise the process so that it makes sense economically.

“Algae is a high volume and comparatively low-value product, so we have evaluated 10 separate species and different growing conditions to see which achieves the best results. Next, we’re keen to find partners from other adjacent sectors to work with and explore the collaborative opportunity where we each get what we need from different parts of the plant and make the entire process more circular.”

Liz Fletcher, director of business engagement at IBioIC, said: “The results of this project could lead to exciting new opportunities for feed supply chains based here in Scotland that reduce our reliance on imported ingredients from overseas. In some cases, one industry’s waste is another’s gold, so it would be great to see different sectors working together to extract value from one core raw material in a shared and sustainable fashion.”