Taking the Maine road

The US national aquaculture regulations could benefit from following the regulations used in Maine, according to a new film.

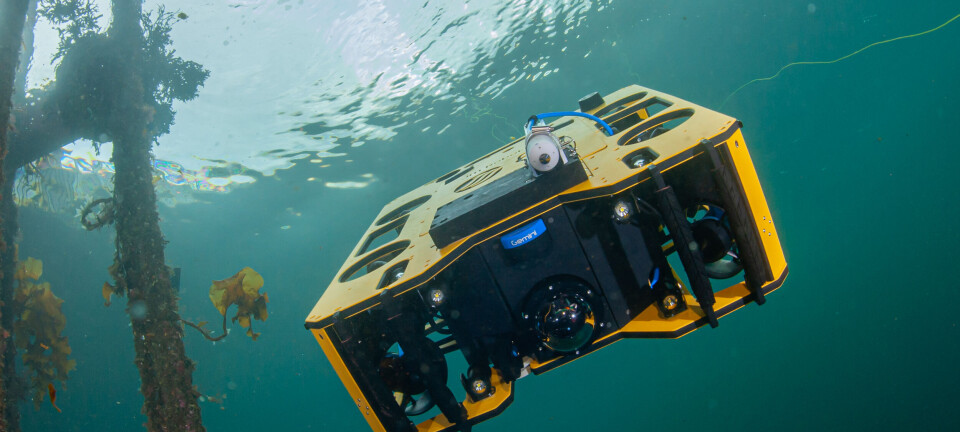

A short film by Living Oceans Productions and funded by the US Soy Aquaculture Alliance, discusses the challenges to creating a robust aquaculture industry in the US.

Over 90% of fish and seafood consumed in the US is imported from overseas, and over half the imports are farmed. On a global scale, the US aquaculture industry only produces 1% of seafood, meeting only 5-7% of the country’s demand. The question asked by the film is, why doesn’t America grow more of its own fish and seafood?

“We are a business that is based on research and development,” said Sebastian Belle, the Executive Director for the Maine Aquaculture Association.

“We have tremendous research and development assets in this country…all of this research is important for us to be able to develop the sector.”

But the irony is that much of this research is being used and commercialized in other countries because of the time it takes to get an aquaculture business up and running in the US.

“We work every year to try and help regulators to develop the regulations so that they work, but also so they are not so onerous that we can’t do business,” explained Belle.

Because they have had so much experience with permitting and leasing, the state has the shortest permitting time in the country. Now Maine is recognized for its innovative development of sustainable aquaculture and coherent, coordinated permitting. But these systems have not been adopted on a national-level.

Western freeze

“There hasn’t been a new salmon farming license issued in Washington for over 20 years,” said Alan Cook, VP of Aquaculture for Icicle Seafoods. “The process for applying for a permit is extremely challenging, very expensive, slow, and there is no certainty in the system.”

Employing 50 people on 3 different farms in Puget Sound in the Pacific Northwest, Icicle Seafoods produces about 10 million pounds of Atlantic salmon per year.

But all told, the US produces only 10% of the 450 million pounds of farmed salmon it consumes each year.

“There is no biological reason – it’s purely a political barrier to us investing in the industry and growing it to the extent we want to have it.”

For now, that presents too much of a challenge for farming in Washington State - access to farm sites is so limited, that the long-term viability of the business is uncertain.

“What we need is a coherent permitting system that will allow us to invest in the science required to vet a new site and go through all the legal applications that need to be put in place to get a site happening,” he said. “We have an extremely complicated permitting environment. If we could simplify that, it would go a long way to promoting the kind of investment that is out there for salmon farming.”

“It’s important for us to not re-invent the wheel nationally,” said Belle. “We could do what we do here in Maine at a national level, and make it work.”

“We need a national aquaculture economic development program, like we have a space program…We need a program that targets commercial aquaculture economic development, and not a program that focuses on research alone. That is what we have lacked in the country,” Belle concluded.