'Imbalance still exists in coastal community voices'

Well organised anti-farming groups make more noise than other locals, government science advisor tells MSPs

A scientist who advises the Scottish Government has told MSPs that there is an “imbalance” in how different sections of communities are sometimes represented on the issue of new salmon farms in their areas.

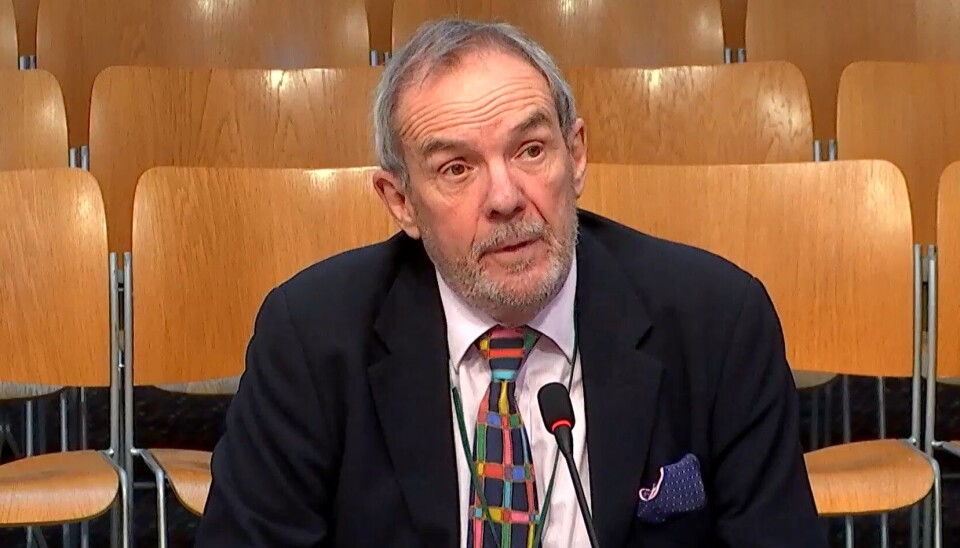

Professor Nick Owens, a member of the Scottish Science Advisory Council (SSAC), made the observation to the Scottish Parliament’s Rural Affairs and Islands (RAI) Committee today during an evidence session held as part of an inquiry into the salmon sector.

Owens, director of the Scottish Association for Marine Science (SAMS), was quizzed about the SSAC’s report, “Use of Science and Evidence in Aquaculture Consenting and the Sustainable Development of Scottish Aquaculture”, published last year.

The report was requested by Rural Affairs Secretary Mairi Gougeon following 2022’s independent review into aquaculture regulation by Professor Russel Griggs which flagged up “mistrust and vitriol” between fish farmers, regulators, and consenting bodies, and said the system was not fit for purpose.

Well resourced

In an appearance before the RAI Committee’s predecessor, the Rural Affairs, Islands and Natural Environment Committee, in 2022, Griggs said those opposed to fish farming in coastal communities didn’t speak for everyone.

“It’s quite clear from the work I did on this [review] that the ‘anti’ voice in some places is very well funded, it’s very well resourced, which perhaps the local voice isn’t. So, it’s about trying to bring in to that some balance so that we understand when we’re listening to voices that it’s not just the loudest that should get their way, but it should be one that’s based on evidence,” said Griggs.

That assertion was repeated by Owens to the RAI Committee after he was asked what the SSAC meant when it referred in its report to “a lack of shared arenas for voicing concerns and dialogue which continues to fuel a perception of secrecy and misunderstandings”.

Lack of trust remains

“As part of the data gathering for the report we engaged with the wide community, from the industry right through to campaigning groups, and there’s no doubt that that lack of trust is still there. Partly, I suspect that whatever one could do, there will always be an element of that because people have taken entrenched views, it is an incredibly binary view out there,” said Owens.

“But I do believe, and we felt when we were writing the report, that some structured approach to trying to break down those barriers could be helpful.”

Owens said that scientists in all fields were starting to listen to stakeholders as well as talk to them, and that “the whole technique of science engagement is growing rapidly”.

Improvement is possible

“In one of our round table discussions (to gather views for the report) there was a very heartening and very civil discussion and exchange of views, and I believe the meeting ended more successfully than it started. So, it is possible to improve the situation.”

But he added: “An important observation was that certain parts of the community are very well organised and are very well funded, and that much was evident in the sorts of data that were brought to the table in the consenting process. There is definitely an imbalance at times between the voices.”

Rhoda Grant said that in the SSAC report, the need for the precautionary principle to be “socialised” was identified, and asked what that meant.

Risk is always there

“The problem with the precautionary principle is that if you took it literally, very few of us would get out of bed in the morning,” said Owens. “Risk is always there, so the notion of socialising it is to introduce the pragmatism that is really necessary here.

“There will be people, and we know it, we heard from them in our interactions, who would say there is a risk in aquaculture, in salmon farming for instance, and therefore it just should not happen, full stop. And so, the notion of socialising is another way of saying that we need to engage properly so that there is a better understanding of what uncertainty and risk is all about.”

“Do you think that precautionary principle is influencing consenting at the moment? Are we being too careful, and to things have to change,” asked Grant.

There is also reality

“The precautionary principle is to a certain extent embedded in consenting,” replied Owens. “Whether it’s too much or too little, I don’t think I could say.

“I think what we were trying to say is that the precautionary principle is a good principle to have, but there is also reality, and how one can get a better balance of the precautionary principle is to better understand things like risk and uncertainty.

“There will always be a continuum of people from those who would say that the precautionary principle says that we should not do anything, to those people who say that we can do this much, but only this much, and there are others who are prepared to go further. There isn’t a right answer to that.”

“So, where the tensions lie, this might not solve that problem,” said Grant.

Difficult and challenging

“It might not, but our hope was that by improving the communication, and having more formal arrangements, there would be a greater understanding by more people and more members of the community about really how uncertain an awful lot of the principles that lie behind things like consenting, how difficult and challenging it is,” said Owens.

Earlier, Owens pointed out that knowledge gaps remain in the aquaculture sector, and that it would be “not unreasonable” to the salmon farming industry to pay for more research via a levy, as happens in Norway.

“It does help in itself - it does its own work and through partnerships through, for example, the Scottish Aquaculture Innovation Centre - so the industry do contribute but there is something to be said for perhaps looking at that,” said Owens.