Researchers may have developed an effective salmon lice vaccine

The vaccine works well in the lab. Now fish will soon be put into the sea to be tested there.

A small Norwegian team led by a veteran scientist has developed a vaccine that has proved to be effective against salmon lice in the laboratory and will soon be tested in the sea.

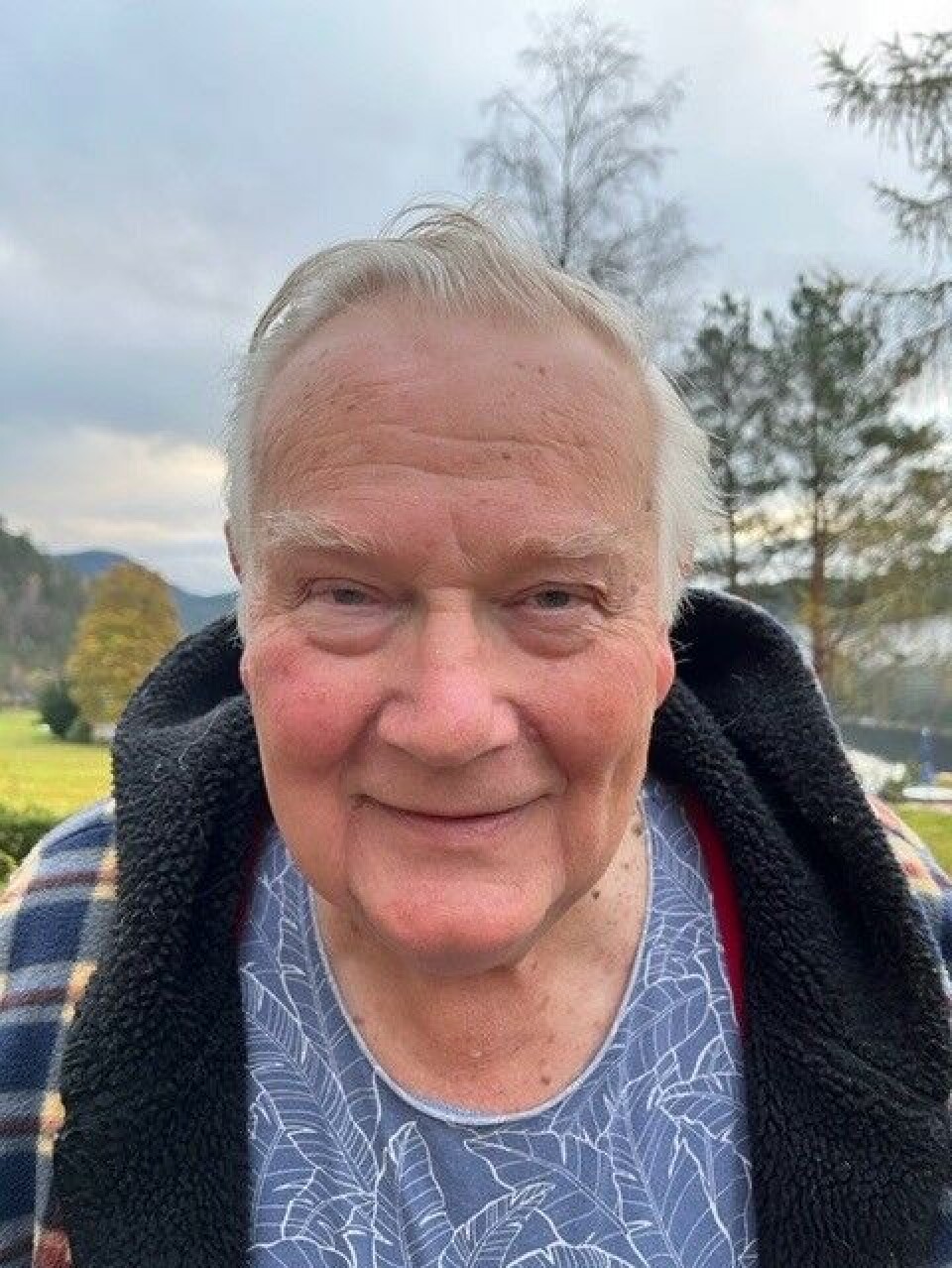

Erik Slinde, former director of research at the Institute of Marine Research (IMR) and research institute Nofima and associate professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (NMBU), was given close to NOK 1 million from the Western Norway Regional Research Fund around three years ago to try to create a vaccine against lice.

He has made good progress since then.

“We have fish swimming in tanks at the IMR’s research station in Matre, vaccinated with salmon lice vaccine, which will be released into the sea in November,” he told Fish Farming Expert’s Norwegian sister site, Kyst.no.

Expert team

The 76-year-old is confident that the results will be good, “although we always have to add the caveat that results from the lab are not always the same in larger conditions at sea”.

Slinde has been helped by Professor Bjørg Egelandsdal at NMBU and Amritha Johny, a post-doctoral researcher at Nofima who has participated in her spare time.

He has also recruited Ole Petter Krabberød, a man with many years of experience in aquaculture and other industries. Krabberød has invested in the project and handles all the commercial and financial aspects, said Slinde.

The vaccine has been developed by identifying proteins that lice inject into salmon, which was achieved by taking blood from fish that were heavily infected with lice, then analysing it with the latest methods: liquid chromatography coupled to double mass spectroscopy (UHPLC-MS-MS).

The researchers found more than 300 proteins, of which 58 were from lice. Of these, two proteins were selected as possible vaccine candidates, i.e., antigens.

Peptide vaccine

“We do not need to use the entire protein as antigen, it is enough to use a piece. Here one looks at the spatial shape of the protein and selects a piece of the protein on the surface. This piece can be produced in the laboratory. We have had this done in England at ProImmune Ltd,” explained Slinde.

The vaccine type is therefore a peptide vaccine, which is of the type that is now being developed as a second-generation coronavirus vaccine and which should be able to work against a wide range of Covid variants.

Testing has been carried out at IMR in Matre, with one tank containing 40 vaccinated salmon and another with 40 unvaccinated as a control. About 80 infective-stage lice were added to each tank, and approximately 20 stuck to the vaccinated fish.

“All fish that were not vaccinated had to be killed due to excessive lice load before the experiment was finished, in accordance with the laboratory animal regulations,” said Slinde.

“At the same time, all the vaccinated fish survived, and also had few lice at the end of the experiment. This provides 100% protection in terms of survival and a 70% reduction in the number of lice.”

Slinde said that the vaccine also works well against lice on rainbow trout.

Tests at sea

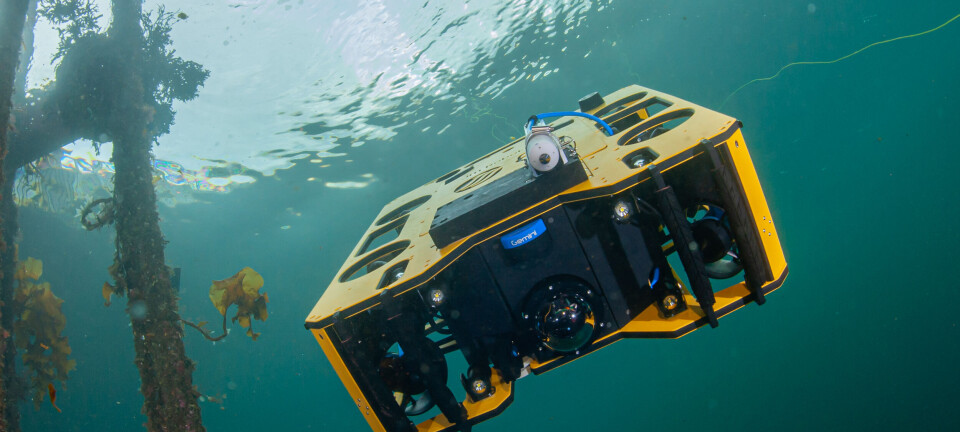

The next step is to have fish tested in the sea under natural infection conditions.

“The Norwegian Medicines Agency requires that a test be carried out on a small number of fish in the sea. This is to test that the vaccine provides protection in natural surroundings and that the fish can be eaten,” said Slinde.

“We have now vaccinated 2 x 8,000 salmon against lice that are to be released in two cages, and the same number of unvaccinated salmon in two control cages. The fish are now going into tanks at Matre and will be released into the sea in November. In parallel, we are working to be able to document and get approval that these fish can be slaughtered at 4-5 kg and sold as food. It is important not only for further experiments, but also for financing the experiment.”

Slinde and his colleagues have also requested a meeting with fisheries minister Bjørnar Skjæran to ask him to speed up approvals, as was done with the approvals process for Covid vaccines.

“Remember that salmon lice treatment directly costs the industry more than NOK 10 billion a year,” said Slinde. “In addition, there are the fish welfare problems and all the associated costs of the fish getting sick or dying because of what they are exposed to. We believe that procuring a salmon lice vaccine quickly, and which is documented to work, is in the national interest.”

Full-scale use

Having the vaccine tested on a full scale will be the last step before commercialisation.

Two independent salmon farmers – one in western Norway, the other in Trøndelag – are interested in testing the vaccine.

“But first, the Norwegian Medicines Agency must approve. And it must be clarified whether the amino acids that we use in themselves are a chemical or a medicine. It will matter which laboratory can produce it. If they require a so-called GMP laboratory, it can be expensive. But the amino acids we use are already present in salmon which are infected with a lot of lice, so it should be safe,” said Slinde.

The vaccine has already been tested in Chile, and resulted in a 92% reduction of Caligus rogercresseyi, the species of louse that causes problems there.

Slinde believes that if the last steps in the process now turn out to be successful and they get permission from the Norwegian Medicines Agency that the vaccine they have made produces fish that can be safely eaten, a vaccine for the industry could be ready before too long.

“We are working intensively. I have never worked as much as I do now, not even when I was an employed researcher. So, at best we will have something commercially ready by spring 2024. At worst not before 4-6 years from now. Remember that I am 76 years old now. This must be ready before I'm 80, that’s the goal,” Slinde said with a chuckle.