SEPA sea lice model will damage fish welfare warns Mowi Scotland chief

Environment watchdog's calculations over-predict parasite numbers ‘possibly by a factor of 4-5’

The boss of Scotland’s biggest salmon farmer has warned that the Scottish government’s sea lice modelling method hugely over-predicts sea lice concentrations and could lead to farmed fish being harmed.

Ben Hadfield, chief operating officer of Mowi Scotland, said that if the model used by the government’s Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) is not changed, it will force unnecessary lice treatments of farmed salmon that will challenge their welfare.

Mowi’s head of oceanography and environmental monitoring, Dr Phil Gillibrand, has developed his own sea lice model for Mowi as part of its successful application to grow post-smolt salmon at a farm in Loch Etive. Mowi said he has collaborated with SEPA, Marine Directorate and other scientific institutes to achieve a robust and transparent model architecture.

Validation process

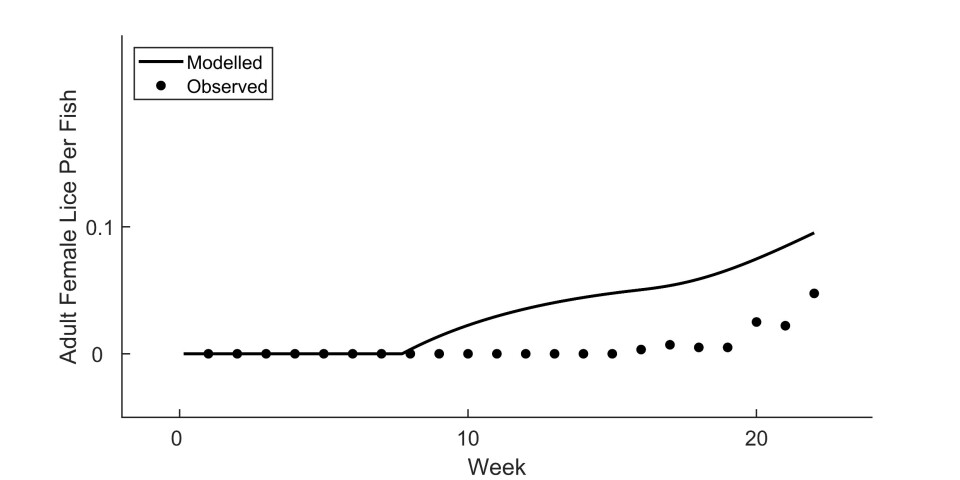

The initial validation of sea lice modelling in Loch Etive, which was done with the largest ever deployment of post-smolt salmon (2.5 million), shows that Gillibrand's model has good accuracy, but still over-predicted sea lice levels in the first five months of stocking.

Gillibrand said: “We used a sea lice dispersal model to establish the connectivity between our farm sites in Loch Etive and neighbouring sites, and then combined that with a population dynamics model to predict the lifecycle of the lice on the farms and estimate the daily production of lice larvae. Both models include a degree of precaution, and the lice count data we are collecting will help fine-tune the models and improve the predictions in the future.”

Hadfield and Gillibrand visited the site in mid-July to analyse and validate the model against sea lice levels.

“The post-smolt salmon looked excellent: perfect form, healthy gills and low sea lice levels,” Hadfield said in a press release. “Our model has a strong correlation to lice epidemiology, but still over-predicts to a reasonable level, due to the precautionary assumptions in line with the disciplines expected in environmental modelling such as the fact that we are not able to model the full extent of our farmed cleaner fish removing sea lice from our salmon.”

Sea lice modelling now forms a big part of regulation in Scottish salmon farming due to SEPA’s Sea Lice Risk Framework (SLRF) where the migration of wild salmon through salmon farming regions on the West Coast is modelled. This was first suggested by the salmon industry as part of the Salmon Interactions Working Group as a practical way of improving the relationship between the industry and wild fish interests.

Three to six years

Hadfield believes that a robust and validated model which predicts sea lice levels is an important part of the world leading aquaculture regulation but warns that it will take three to six years to do it properly and accurately, even with the intense resource deployed by Mowi Scotland in the case of Loch Etive.

I was disappointed to see Wild Fish and CCN state that sea lice levels were high and uncontrolled when the data shows they are at the lowest level for 20 years ...this evidence was at best misleading and given with the express intent of damaging the salmon farming industry

He is critical of what he describes as “ultra-precautionary and therefore unrealistic model architecture” that has been presented by wild fish environmental non-governmental organisations such as angling pressure group Wild Fish, Costal Communities Network (CCN), and Fisheries Management Scotland, which recently gave evidence to an inquiry into salmon farming progress being held by the Scottish Parliament’s Rural Affairs and Islands Committee (RAIC).

“I was disappointed to see Wild Fish and CCN state that sea lice levels were high and uncontrolled when the data shows they are at the lowest level for 20 years,” said Hadfield, who is also COO of Mowi’s operations in Ireland, Faroes, and Canada East.

“I believe that this recent evidence was at best misleading and given with the express intent of damaging the salmon farming industry. Indeed, this was duly refuted by Charles Allan, the most senior operational regulator at the Scottish Government, who gave evidence to the Parliamentary Committee that sea lice were under control and at low levels.”

What SEPA’s SLRF Screening Model shows is that out of more than 220 operational salmon farms in Scotland only 19 have a theoretical risk, according to a model that vastly over-predicts effect, he said.

Hadfield said that while Mowi and Fisheries Management Scotland (FMS) agree that a robust and validated model is a major step forward, FMS failed to make important points to the RAIC.

“The current SEPA model over-predicts sea lice concentrations, possibly by a factor of 4-5, and uses a very low impact threshold which equates to detectable effects on wild salmon smolt behaviour but not levels that would induce high mortality. It assumes all salmon farm biomass is constantly at its maximum, which it is not and, crucially, it is yet to undergo full validation to remove layer upon layer of over-precautionary assumption in order to attain a realistic correlation,” said Hadfield.

Unnecessary treatment

“If this is not changed, then it will overregulate and force unnecessary treatment of farm-raised salmon which will challenge the high welfare of stocks, which all salmon farmers work for daily. [FMS] not explaining this clearly and calling for an ever more precautionary and rushed approach is misleading and is designed to achieve an over-prediction of impact. I fervently hope that this can be corrected in future [inquiry] sessions, and we can talk with confidence about the reality of conditions in the sea and how salmon farmers across Scotland understand and adapt their methods accordingly.”