Lump sums

By Rob Fletcher

While still at an early stage, especially compared to their wrasse farming trials, which have proved to be very successful and have yielded good results in sea cages, the project has already shown promising signs, with the first batch of lumpfish proving adept at their job since being transferred from the south coast of England to salmon cages in Scotland last year. Masterminding the project is one of the UK’s most experienced farmers of marine species, Richard Prickett, who previously managed Marine Farms cod hatchery and diversified to wrasse in the wake of the No Catch cod collapse. While Richard is acting as the main consultant, the man on the ground in Portland is Mike Webb, owner of the NMC, who is moving into lumpfish production following 7 years providing specimens for aquaria across the UK and further afield. As Mike explains: “NMC is focused on collecting native marine species for institutions focusing on the direct education and research of marine life. We like to think conservation starts at the source people need to be aware of what lives in our waters and how we can manage the seas with realistic data to fish sustainably and prolong the life of our seas for future generations. “Over the past 4 years we have supplied Machrihanish, Otter Ferry and Ardtoe with ballan wrasse broodstock and we’re currently setting up a pilot project to aid the scallop farming project in Lyme Bay.” “There is a need to gain more knowledge understanding between the marine sector – national aquaria display fish but have little idea of how to catch them, fishermen are great at catching fish but have little understanding how to keep a fish alive. We work with a specialist team of fishermen utilising considerate methods to ensure our collections are kept in good health.”

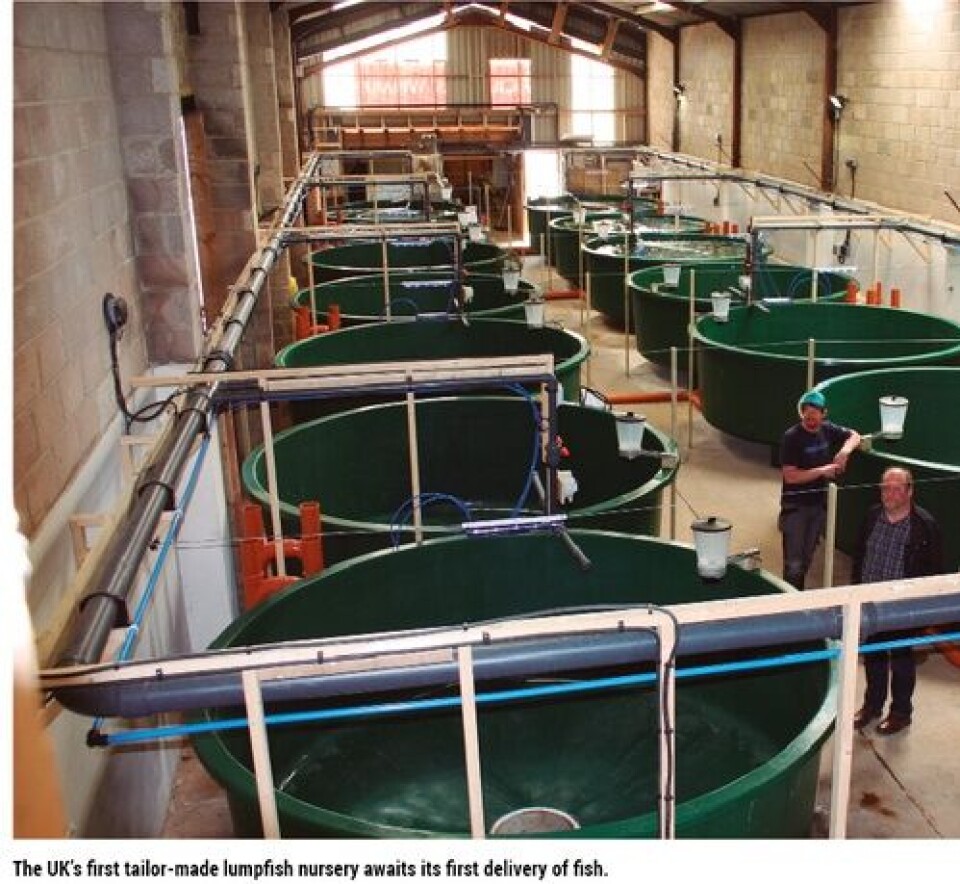

Although an official agreement has yet to be signed, the project is likely to be a joint venture between Marine Harvest and the NMC – combining the financial clout of the former, with the local knowledge of the latter, although the NMC are happy to keep things on a relatively tight budget, as is clear from the number of cunningly recycled parts in the UK’s first purpose-built lumpfish nursery, and by the fact that Mike has been able to complete most of the construction work – converting an old lobster and crab distribution warehouse – himself. It may at first sight appear an unlikely alliance: the set-up at Portland could hardly contrast further from Marine Harvest’s state-of-the-art hatchery at Lochailort – indeed, much of it has been cannibalised from existing hatcheries (such as Machrihanish and even the old hatchery at Lochailort itself) – but it’s a partnership that appears to be as symbiotic as that of the lumpfish and the salmon they clean. Indeed the project is helping the NMC retain their 5-strong staff – who were previously operating on a more seasonal basis tending fish for aquaria – year round, while Marine Harvest are benefitting from using an existing site, manned by enthusiastic and adaptable staff with previous knowledge of the species, that requires a comparatively humble budget to run. Rio Lightowler, Hatchery Manager, is delighted by the project and its range of positive impacts. “As a marine biologist, I understand what relief cleaner fish have given to the oceans, reducing the volume of chemicals and treatments used. I think using cleaner fish is an improved way of managing the sustainable fish farms,” she reflects.

Ian Prendigast, who is going to be involved with the nursery side of things, agrees: “I think they’re a really funny fish and great fun to work with. It’s nice to know we are working to make a difference”. “It’s a marine species, needs a marine rearing protocol, which is very different from salmon and we could also offer premises that were already up-and-running,” Richard reflects. Richard established a hatchery and nursery in Portland Port following the successful spawning of wild-caught lumpfish during 2013 and the newly-established nursery facility now boasts 14 7-tonne tanks. The NMC’s first batch of 13,000 fish was sent to Scotland in 2014, while Richard is planning on sending 200-250,000 10 gram fish north over the course of the year. “Marine Harvest have been very happy, with the results so far and Ronnie Hawkins, MH’s Cage Manager for Cleaner Fish, is impressed with the results to date,” Richard explains.

On the trail of wild lumpfish Incredibly, only a handful of lumpfish are required to create the 250,000 offspring desired for each cycle and, according to Mike, 30 females are “more than enough” to produce this volume. This is perhaps fortunate given the difficulty facing fishermen hoping to target the species. Indeed, despite the fact that Mike has a pool of proven inshore netsmen, who are well-versed in catching specimen fish, at his disposal, it’s not overly easy to either locate or capture this enigmatic and intelligent species. “One of the fascinating things about lumpfish is that we know so little about them,” Mike enthuses. “You see lumpsucker juveniles around here from April to June, and they’re thought to migrate to the Atlantic shelf a few weeks after they’ve hatched, but no one is really sure where they go”. “This doesn’t make it easy for the fishermen – they might have five or six miles of nets out at any one time for the lumpfish and only catch 5 or six fish per day.” “Often they put out five lines of nets and the lumpfish will dodge past the first four before being finally being caught,” he adds.

Mike has a great respect for the fishermen and their knowledge of the area: “These guys in my opinion have the best understanding of our seas and need more support. With the correct guidance these guys can provide realistic data to help eliminate unrealistic quotas and manage and survey our waters sustainably,” he reflects. While the location of the hatchery might seem a little distant from Marine Harvest’s salmon sites, which are scattered across the north and west coasts of Scotland, the knowledge of the Dorset fishermen and their proximity to wild lumpfish stocks is another key advantages of the Portland site, and Richard is quick to point that this is where Mike’s expertise and local knowledge really come in to their own. “We’re closest to the UK’s biggest lumpfish fishery and Mike has good fishermen at its disposal. We’re looking for a Scottish source but the problem might be that most of Scotland’s inshore fishermen use pots to catch lobster and crab – while pots are good for catching wrasse, we need fishermen practised at using inshore nets to catch the lumpfish,” Richard reflects. “My feeling is that they’re right up and down the coast,” Mike adds. And as a result he is planning to travel north with some Dorset fishermen to try and locate other, as yet untapped, sources of lumpfish roe.

Hatching After being captured the lumpsuckers are deloused, then allowed to breed naturally in barrels before the roe is taken to the hatchery – the females are released while one male is left in each barrel to guard the eggs, which are placed in upwelling buckets. “We allow them to spawn naturally in barrels sunk 3-4m down in the harbour. We tried stripping but found it difficult to get the milt from the males,” he explains. “In Norway they have been able to strip the lumpfish, which gives them a more even hatch and one of the biggest challenges we face is making sure that all the eggs in each egg mass are allowed to develop, which means you have to break them down into smaller clumps by hand,” Richard adds. The lumpfish eggs are about 2mm long, hatch within 30 days and are fed Artemia nauplii – which are hatched on site – for their first two weeks post-hatching. “We also use the Otohime diet, but given that lumpfish aren’t very fussy, we’re likely to look into using cheaper foods,” Richard points out.

“I’m sure there will be disease issues, and we use a dip vaccine against pasturellosis, furunculosis and vibriosis when the fish are 1-2 grams. This lasts for about three months and protects the fish until they are in Scotland – at which point they are likely to receive an injection vaccine. “One of the advantages of the RAS system is that biosecurity is much easier to control, than in Norway, where all the systems operate on an open flow basis and disease issues have been more of a problem. However, there are still a number of factors that we don’t know too much about, such as the effects of pH and diets and which we need to refine,” he reflects. Richard stresses that, in time, it’s likely that MH will use more than one hatchery, so as to enable them to extend the spawning season and thus produce several generations over the course of a year. “In Norway, where lumpfish research is 2-3 years ahead, they’ve worked out that there are at least three distinct times when the lumpfish spawn naturally – depending on where on the coast they’ve been captured, which allows them to extend the breeding season to about 9 months of the year. “We think this is likely to be the case in the UK too and if we can find other populations, this will help them to prolong the production season. In order to increase both the length of the spawning season and the overall volume of lumpfish produced, it’s likely that Marine Harvest will use several other hatcheries – such as the one run by Alastair Barge at Otter Ferry, and the one previously part of the Anglesea Aquaculture project in Wales too,” Richard predicts. In the longer run, of course, lumpfish producers will want to emulate the wrasse industry and have their own domesticated broodstock to breed from but – at the moment – if appears that this will take a few more years.

Indeed, Richard points out that even in Norway they have yet to succeed in this goal, although SalMar, he says, are preparing to make this next step. “It normally takes 5-6 years before you can domesticate a new species and develop your own broodstock,” Richard explains. However, as Richard and Mike add, while lumpfish are easy to raise as juveniles – they have already got a survival rate of over 50% at the NMC, despite only raising a couple of batches – they don’t seem to fare too well in extended captivity and it’s not proved possible to retain wild broodstock. Indeed, Richard adds: “There have always been problems with producing market-sized fish in recirculation systems”. As a result, and because they’re keen to ensure that they’re not having a detrimental effect on the wild stocks, the NMC’s broodstock are now tagged and released after one spawning. “While we could keep them captive for a second spawning, their first spawning seems to be by far the most viable. What’s more, we know so little about lumpfish and we need to ensure we’re using them sustainably,” Mike observes, “and hopefully our tagging programme will help us understand them better.”

Future plans It will be interesting to see how lumpfish production evolves in the UK but, according to Richard, the majority of Norway’s wrasse projects have since moved on to lumpfish, as “wrasse need greater resources, and are only really financially feasible for the big boys.” As long as they continue to prove effective at eating lice in the cages, it seems likely that this trend will be mirrored in the UK. Given the amount of funding that wrasse projects have received in the UK, Richard is also hoping that lumpfish might also attract some form of financial backing – and it does appear to be a worthy subject for consideration for funding bodies such as the Technology Strategy Board, NERF or (for any lumpfish projects north of the Border) the Scottish Aquaculture Innovation Centre. “We can’t learn everything from Norway – we need to generate our won knowledge of local conditions and local lumpfish stocks,” Richard reflects. Either way it appears that the nascent lumpfish industry is proving to be an inspiring model and one that’s strongly reminiscent of the early days of the salmon industry – peopled by gifted, enthusiastic, pioneers, who need to learn quickly on the job. “One of the most satisfying things about the project is that, although all our staff are new to the aquaculture industry and come from backgrounds in aquaria, within our first full year they’ve managed to adapt so well – I asked Mike to run the nursery because he built the bloody thing!” Richard points out. And the other satisfying thing about cleaner fish production is the degree of openness and collaboration between industry players. “Because it’s not a commercial food fish all the industry is co-operating, and everyone is fighting for the greater good, which is very different from my cod farming days,” Richard concludes.