Looking back, thinking ahead:

Richard Darbyshire

Fish Farming Expert has asked individuals connected to the salmon farming industry about their 2024, and what they hope for this year. Today we feature Richard Darbyshire, regional production manager Shetland for salmon farmer Scottish Sea Farms.

What were the highlights for Scottish Sea Farms in 2024?

There has been a lot of positive change in Shetland in the past 12 months that I’m immensely proud of. It’s three years since the purchase of Grieg Seafood and we’ve just set new records in the first cycles completed to Scottish Sea Farms production plans. The Gonfirth area was up by 600 tonnes on the previous best production volume and the Setterness area is up by 1,700 tonnes, with the fish reaching 5.7 kilos after 13 months in the water.

The harvest and production volumes for the whole Shetland region in 2024 were better than budgeted and so was harvest size. These great results are down to the really strong teams that have developed. It’s rewarding to see the two previous different company cultures gelling together and acting with the same focus and mindset.

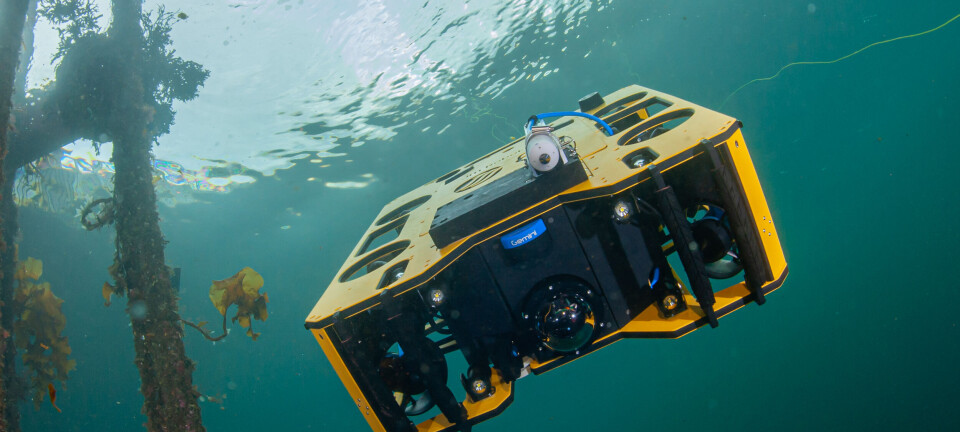

Decisions we’ve made as a company, with investment in freshwater treatment vessels and FLS delousing systems, have been a significant factor in nullifying the risk from sea lice and amoebic gill disease (AGD). Investment in our hatcheries at Girlsta and Barcaldine, and in Shetland processing, have also played an important part in this improvement, with larger, better quality and more robust smolts and the ability to increase harvesting capacity should a fish health issue arise.

And we have modernised more of our marine farms in a drive to reduce stocking densities and ensure every fish is given the best opportunity to thrive.

What are the most significant challenges and opportunities for Scottish Sea Farms this year?

The biggest challenge is climate change. There is a method in my madness moving north, from the mainland, where I initially started my career, to Orkney for 14 years, and now to Shetland; as the water temperatures increase, I’ve headed further north to seek cooler water temperatures.

However, despite this, all our farming areas are now seeing warmer seas and more plankton and jellyfish blooms.

In our plankton lab in Shetland, we analyse water samples, collected daily from every farm, and we have rolled out a harmful plankton action plan and new training courses to improve awareness and ensure correct mitigation.

We have developed a traffic light system with key thresholds set for different plankton, hydrozoan, and jellyfish species. Every manager knows the trigger levels and makes decisions based on these, such as pausing feeding to keep fish lower down in the water column or activating aeration if required – for example, should oxygen drop when plankton respire at night.

In an ideal world, we would choose to handle fish as little as possible, however the incoming Sea Lice Risk Framework will inevitably lead to more fish handling events.

Richard Darbyshire

The key goal for 2025 is to develop larger farms in better locations, with deeper waters and faster currents. We want to sustainably increase production tonnage, increase employment opportunities, and increase both direct and indirect spending in local communities.

We’ve already been successful in getting one new farm in Shetland this year, Billy Baa, and we’re hoping to finalise plans for a second farm in the New Year.

Additional opportunities include the development of post-smolts and putting larger fish to sea with shorter growing periods, amongst other innovative approaches.

What do you see as the most significant challenges for the salmonid farming industry in Scotland and globally in 2025?

A few years ago, I would have said sea lice and AGD, but having largely mitigated these challenges, what we are seeing now is increasing levels of winter lesions, viral diseases and seal predation.

The grey seal population is steadily increasing in the Northern Isles and their constant attacks on our fish, even if they don’t infiltrate the nets, increase stress and make them more susceptible to disease.

We are trying to reduce seal predation by installing double nets, but this is a costly process, and we have also had to significantly increase our net washing capacity for all the extra nets that need to be cleaned on a weekly basis.

Meanwhile, the development of vaccines for CMS (cardiomyopathy syndrome) and HSMI (heart and skeletal muscle inflammation) is slow, and winter lesions are exacerbated by handling the fish. In an ideal world, we would choose to handle fish as little as possible, however the incoming Sea Lice Risk Framework will inevitably lead to more fish handling events.

Salmon farming is very highly regulated, more so than any other farming sector, and I do feel that we are over-burdened by red tape, which not only slows down growth but also brings extra costs and makes Scotland uncompetitive.

A more streamlined regulatory system that supports our businesses and, in turn, supports rural communities, is long overdue.

Tomorrow: Justin Watson, chief operating officer Scotland and Ireland for fish health company STIM.