Study: Microplastic captured in salmon gills and cells

Researchers in Norway have found microplastics in gills from farmed salmon, and seen that this type of plastic can be “eaten” by the body’s cleansing cells.

Since the start of the plastic production in the 1940s, plastic has become an extensive global pollution problem, including in the form of microplastic - plastic pieces with a diameter of less than 5 mm – according to an article on the Norwegian Veterinary Institute website.

There is growing interest and concern for microplastics in marine aquatic sediments worldwide. Unlike larger plastic, which can easily be seen in the stomach and intestines of birds, marine mammals, shellfish and fish, scientists know little about the extent of spreading, uptake and consequences of microplastics for animal health.

Pilot study

The Veterinary Institute and research organisation NORCE, Stavanger (www.norceresearch.no) conducted a pilot study on farmed salmon this winter. The purpose was to see if microplastic could bind to the gills and thus be an indicator of what type of microplastic the fish had been exposed to.

The gill samples were collected from a fish farm by Åse Garseth at the Veterinary Institute, and chemical analysis of the microplastic composition was performed by Alessio Gomiero at NORCE.

In some of the samples, small amounts of polyethylene (PE) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) microplastic were found. It is not possible to know from the analyses whether these plastic particles were on the outside or were taken up by the cells.

It is important to find out if these particles can be absorbed through the gills and transferred to the blood, or if they are just 'stuck' on the outside. Further studies will show whether such particles can damage the gills.

Macrophages attack

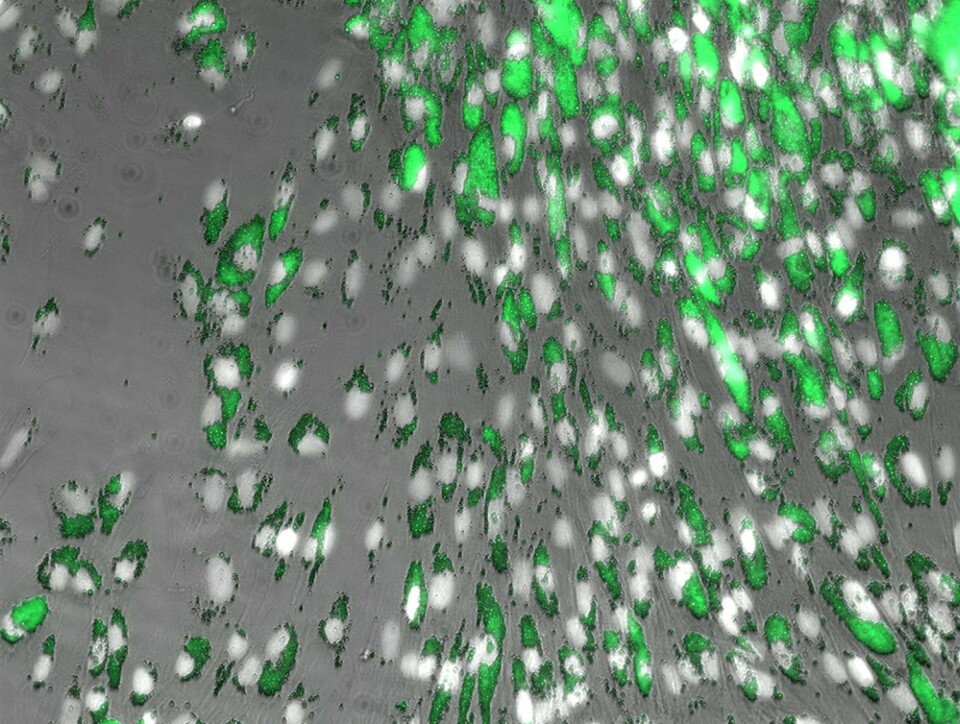

Researchers Maria Dahle and Anita Solhaug at the Veterinary Institute have conducted a pilot study to find out if macrophages, which are a type of immune cells that clean up foreign substances that have entered the body, can absorb microplastic. Atlantic salmon macrophages were exposed to microplastics (polyethylene) in two sizes: 1-5 µm, the size of bacteria, and 10-22 µm in diameter, approximately the size of a cell in the body.

The experiments show that the smallest plastic balls were quickly taken up by the cells. It took only 24 hours before they could be seen inside the cells, and after one week, 90% of the cells were filled with plastic balls. The large beads, however, were not taken as effectively into the cells, but after a week reserachers could see that groups of cells had accumulated around the microplastic beads.

The balls changed in shape and became rod-like. This suggests that the macrophages actively attempt to break down the plastic particles, even when they are too large to be eaten. It is uncertain what these findings mean for fish health and for salmon as food, but this is something the researchers want to investigate more closely.

Seeking the sources

In a new collaborative project led by NORCE by Gomiero and in collaboration with the aquaculture industry, the Institute of Marine Research and the Veterinary Institute, researchers will investigate possible sources of macro and microplastic in the aquaculture industry. This project aims to identify sources of emissions from the aquaculture industry and study how much of this plastic is left in the surroundings around the plants. Researcher Mona Gjessing at the Veterinary Institute will investigate whether changes in gill tissue from salmon that have gone into these environments can be detected.

The project is funded by Norway’s fisheries and aquaculture industry’s research funding body, FHF.