Wild salmon returns fell by 20% in south of England river

The organisation running a long-term wild salmon monitoring project sited hundreds of miles from the nearest salmon farm has reported a decline in returning wild salmon similar to that experienced in Scotland last year.

The Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) said the estimated number of wild adult Atlantic salmon returning to the River Frome in southern England in 2021 was 459, down almost 20% on its 10-year average.

This drop echoes reports from Scotland and Norway where the 2021 annual salmon catches were the lowest on record.

Better for 2022

The smolt population estimate on the Frome in spring 2021 was 6,635 which is nearly 30% down on the 10-year average. However, the numbers of parr observed during GWCT’s September parr tagging programme was encouraging, so the organisation is hoping the 2022 smolt run will be better.

Anti-salmon farming groups and some angling stakeholders in Scotland allege salmon farms are responsible for disease and sea lice population increases that impact wild smolts, but climate change is the biggest concern for the GWCT.

In its review of 2021, the GWCT says: “The consensus opinion is that the decline [since the 1990s] is caused by problems in the marine environment, such as warmer sea temperatures”.

Oceanic conditions

The GWCT is a founder member of the Missing Salmon Alliance, which is developing a “likely suspects framework” that considers the whole life cycle to understand changes in salmon survival, forecast stock prospects and suggest a framework to guide management decisions.

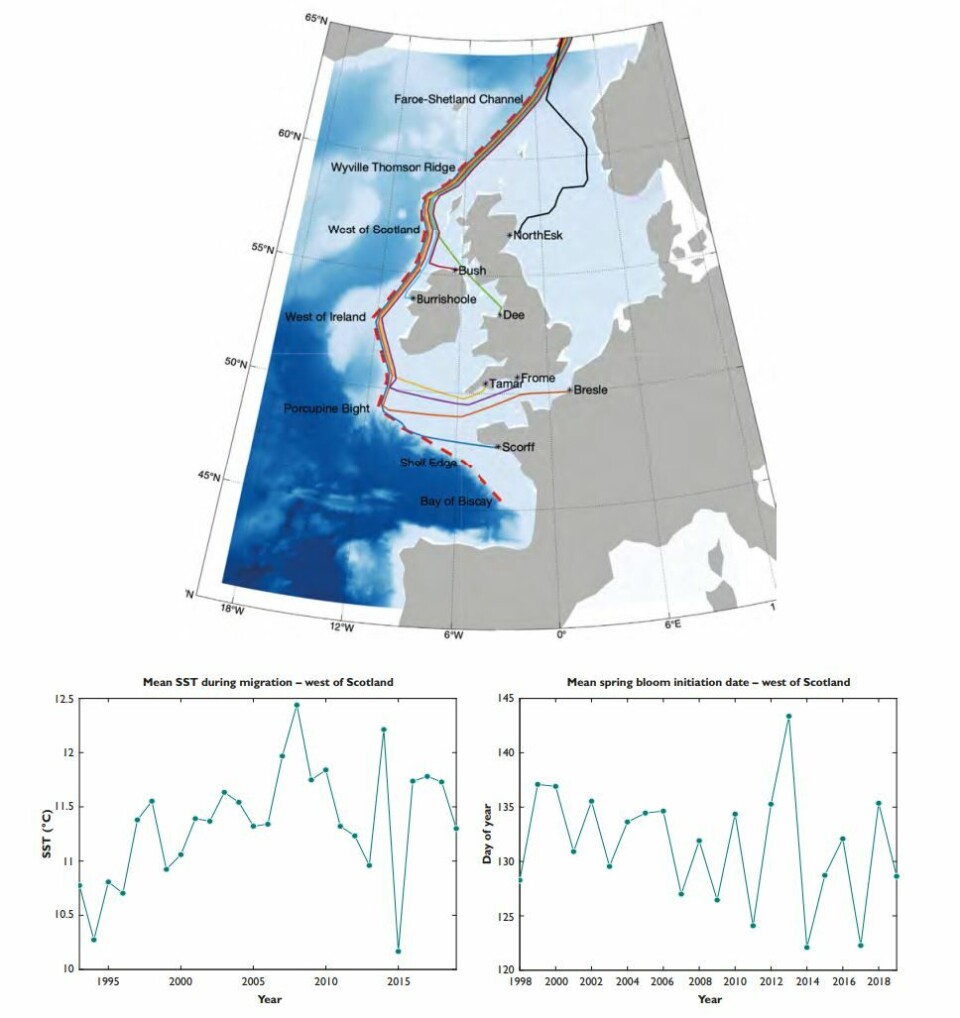

“We are all too familiar with the trend of reduced marine survival of Atlantic salmon over the past decades, and recognise that this is linked to wider changes in oceanic conditions and their impact on salmon growth,” writes post-doctoral researcher Emma Tyldesley, who is working on the framework, in an article in the GWCT review.

Food availability

“The consensus view is that most of the marine mortality and between year fluctuation is likely to take place during the first few months at sea. During this phase the post-smolt actively migrate north to their feeding grounds, they are small and potentially most vulnerable to predators and variations in food availability.”

Researchers have re-synthesised new salmon focused outputs from two oceanographic models, enabling the description of how ocean conditions have changed over the last 20 years at small scale resolutions.

Concurrently they have begun an examination of extensive plankton time series datasets, describing how particular elements of relevance to salmon diets have changed through time.

Zooplankton

“The basic premise for the first part of the study is that post-smolt salmon feed on large zooplankton and small fish during their initial marine migration phase,” writes Tyldesley.

“Identifying signals in these lower trophic levels that relate to past trends in salmon survival might enable development of future indicators or predictors of marine survival of salmon. Possible explanatory variables might include a time lag (i.e., conditions experienced by smolts in one year might be determined by ocean conditions the previous year) and include abundance and seasonal timing of plankton, or larval fish that feed on them.”

The full GWCT review can be read or downloaded here.