Few Pacific Salmon being farmed in Canada

When the commercial production of salmon began in the early 1980’s, it was entirely based on the farming of Pacific salmon- either Chinook (King in the U.S.) or Coho (Silver). The eggs were bought by the industry from surplus eggs collected by government hatcheries that were built to provide additional opportunities for the commercial fishing industry. The B.C. Salmon Farmers Association was coordinating these purchases, and continued to pay for these eggs until a few years ago, despite the fact that by now most of the production is based on Atlantic salmon.

One of the main problems with these species of Pacific salmon was their tendency to mature at a small size, thus resulting in a high cost per pound (or kilo) of production. To deal with this challenge, several strategies were developed- some of which worked while others did not. In the case of Chinook salmon, the industry and government scientists developed a method to produce all-female off-spring after realizing the fact that most of the early maturing salmon if this species were in fact males. Most females would not mature until age 3 or later. One company- Saltstream Engineering- managed to locate a number of Chinook fish that didn’t mature until age four, and they are still using the off-spring of these large fish to generate new smolts and harvest-sized fish. Fish farmers that wanted to produce Coho investigated the creation of sterile stocks, but this was generally deemed to be a failure due to the tendency of these fish to be slow growing and often de-formed (crooked backbones and unusually bulky backs resulting in the nickname “Volkswagen Coho”). Today there has also been developed a strain of all-female Coho salmon, although the amount of production is low and getting lower. Some attempts have been made to grow Coho salmon in freshwater, but with mixed results. One fish farmer from Finland made a valiant attempt to produce large Rainbow trout at a site north of Vancouver on the B.C. Mainland, but most of his fish perished during a large bloom of the Heterosigma dinoflaggelate algae in 1987. This bloom also hit producers in the area that were using Chinook and Coho, but most of the Chinook survived quite well, as they have a tendency to swim close to the bottom of the net pens when not feeding, thus avoiding the highest density of the algae, which usually was at a higher concentration near the surface.

The first Atlantic salmon eggs were authorized for importation to B.C. in 1985- some 130,000 of them originating in Scotland. The following year another 1.1 million eyed eggs were cleared for importation by Canadian authorities, who had to satisfy themselves that there were no risks of pathogens of concern being brought into the country with these egg shipments. Once in B.C., the eyed eggs were again surface-disinfected and placed in quarantine facilities where they were tested for disease prior to being allowed to be placed in ocean farms.

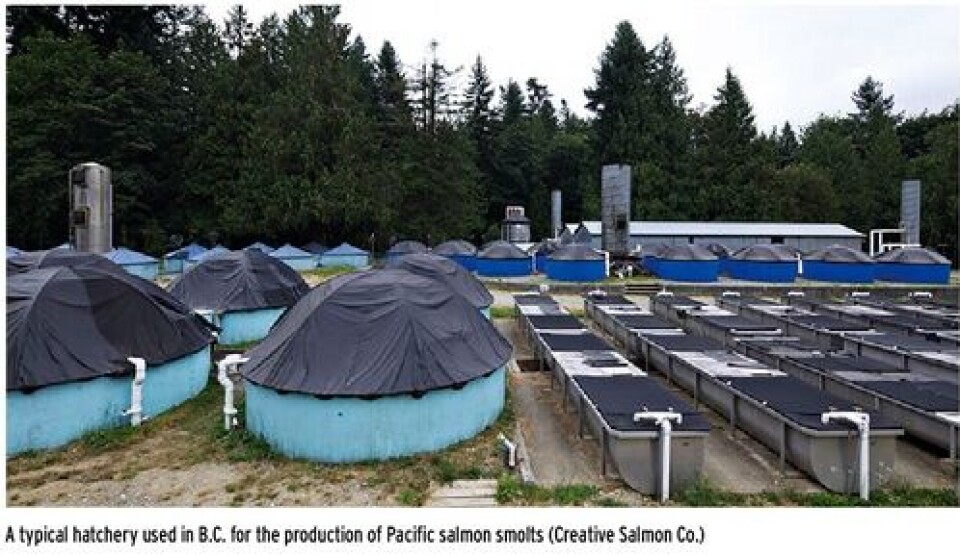

Another part of the Atlantic salmon egg importation story is the fact that earlier this century, the Canadian government brought in over 8.5 million Atlantic salmon eggs and juveniles and placed these in rivers and lakes all up and down the B.C. coast in order to try to establish permanent populations of this species as a popular sport fish. None of these attempts succeeded in establishing populations of Atlantic salmon in B.C. Similar unsuccessful attempts were made to introduce Atlantic salmon down the west coast of the United States until the 1980’s. Since 1985, almost 30 million Atlantic salmon eggs have been authorized to be brought into B.C.- most of them from private facilities just south of the border in Washington State, which in turn got most of their original eggs from the East coast of North America. One of the main suppliers was Cascade Aquafarms, whose fish were named “Cascade”, regardless of the original source of the Atlantic salmon eggs. These fish were reasonably fast growing, but their tendency to swim close to the surface in the pens made them particularly prone to losses during periods of algae blooms. There have been no imports of Atlantic salmon applied for or authorized since 2009. Most of the eggs arriving from Scotland were to come from the McConnell Hatchery, but some of the shipments were allegedly sourced from different stocks- some of which had a very high rate of premature (grilse) salmon. Today there are still some genes left of these fish in the British Columbia salmon farming industry, although the bulk of the genetic material is based on the three importations of eggs from the Fanad Hatchery in Ireland, and locally referred to as being of the “MOWI” stock. These fish are known for their relatively fast growth, good husbandry characteristics (staying deep in the pens, good feed conversion rate and survival). The main sources of Pacific salmon eggs to the industry were the government hatcheries at the Qualicum River and Robertson Creek on Vancouver Island. This genetic material is still being used by the main producer of Pacific salmon in British Columbia, the Creative Salmon Company based in Tofino on the west coast of Vancouver Island. Their relatively modest production is coming from four farm sites whose production methods have qualified the company to sell their Chinook salmon under recently (May, 2012) adopted organic standards for farmed salmon in Canada- the first to do so. General Manager Tim Rundle told FishfarmingXpert that they are growing their smolts to a larger size than what was the norm in the early days of the salmon farming industry in B.C., when it was common practice to send fish to sea pens at a size of 7-10 grams. The larger size means an improved immune system and more complete smoltification.

The same strategy of larger Chinook smolt is also being pursued by the Omega Pacific Hatchery, based just outside Port Alberni on Vancouver Island. Owner/operators Bruce Kenny and Carol Schmitt have been trying to convince DFO hatchery staff to keep their Chinook fry in cold, fresh water for a longer time before releasing them into the ocean. This again in order to improve survival and thus future fishing opportunities. Omega Pacific is also pursuing markets for eyed eggs of Pacific salmon in places like China, Russia, Chile and South America. Mr. Kenny said that the company’s annual egg production capacity in recent years has been increased from about 800,000 eyed eggs to about 2 million today, allowing for the contractual production of some Atlantic salmon smolts to the rest of the B.C. aquaculture industry.

Just outside Campbell River is Yellow Island Aquaculture’s operation- another and yet smaller producer of Chinook salmon, which also claims to be the first producer of organic farmed salmon in Canada (but perhaps not the first to be certified under the official Canadian regime). And on the Sunshine Coast near the town of Sechelt, Target Marine Hatcheries is still running a Coho salmon program amidst a major facility focused on the production of high-priced White Sturgeon caviar. According to General Manager Justin Henry, the company spent over ten years to develop the technology required to produce a strain of all-female Coho salmon- a process which is still undergoing some refinement. There is a lot of interest in this product, which Target Marine now sells to a number of countries in Asia (Japan, Korea) and Europe (Bulgaria, Denmark, Germany, Greece and Romania) as well as to customers in the Americas. This summer, Target Marine successfully managed to produce its first off-season batch of Coho salmon eggs through the management and manipulation of environmental conditions like light and temperature.

The ability to produce monosex strains of Coho salmon allows salmon farmers to push their juveniles to a larger size as smolts, without the risk of generating early-maturing, precocious males, said Henry, who believes that many Coho producers have yet to appreciate the true benefit of using all-female stocks. Just the value of the eggs themselves as a raw material for Ikura production is adding substantial value to the bottom line at the time of harvesting. Target Marine’s eyed Coho salmon eggs are also becoming increasingly popular by international producers as they are certified both organic and free of disease agents by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), which now regulates international trade in such products. The CFIA is in charge of negotiating agreements with respect to the certification criteria required by individual countries. Target Marine has a marketing agreement in place for its eyed eggs with the U.S.- based Troutlodge, Inc.- a major supplier of genetic material for the international aquaculture industry. The company’s goal is to have eyed eggs available for sale throughout the year. Grieg Seafood has been producing a small amount of Pacific salmon in recent years, but according to Director of Production Barry Milligan, the company’s last Chinook salmon are being harvested this week (August, 2014) and their Coho salmon program will be ending later this year in favour of a focus on Atlantic salmon. Grieg has had some previous fish health problems at their hatchery in Gold River on Vancouver Island, but the company has now gained control of the issue, and a new crop of Atlantic salmon is well on their way. Additional security for its future smolt supply is ensured through some smolt rearing and delivery contracts/options with other operators. This exemplifies the relatively close relationship that exists between salmon farmers in British Columbia, where companies like Grieg, Marine Harvest and Cermaq all have various deals going on for the mutual benefit of everyone concerned. For example, Mr. Milligan told FishfarmingXpert that when they had problems with their own in-house smolt supply, some high quality fish were made available from the Marine Harvest smolt rearing facility at Ocean Falls on B.C.’s central coast. Marine Harvest is the largest producer of farmed salmon in British Columbia and elsewhere, and its production in B.C. is- like the other two main producers of Atlantic salmon here (Cermaq & Grieg)- based on genetic material from the Fanad Hatchery in Ireland and the McConnell facility in Scotland- traditionally referred to as “MOWI” and “McConnell”. Marine Harvest gets about 25 million green eggs from its broodstock program each year, which Freshwater Production Manager Dean Guest told FishfarmingXpert are used to satisfy the company’s smolt requirements, which consists of a mixture of S0 (~40%) and S1 (~60%) Atlantic salmon. More than half of Marine Harvest’s smolts now come from facilities using Recirculation Aquaculture Systems (RAS), particularly from its renovated facility at Dalrymple south of Sayward on Vancouver Island. Other major facilities are found by Rosewall Creek farther south on the island, as well as at Ocean Falls on B.C.’s central coast. The company is not particularly set up for the sale of large quantities of smolts, but a few extra are usually produced- “just in case”, said Mr. Guest. Like others, Marine Harvest Canada is also moving away from the production of salmon smolts in freshwater lakes.

Cermaq has the longest history of running a family-based breeding program for Atlantic salmon in British Columbia, which is also based largely on the “MOWI” strain. The company’s production strategy is based on an almost even split between S0 and S1 smolt supply from in-house hatcheries. The current production capacity of approximately 5 million smolts per year might need to be increased if the company’s applications for new seawater sites are approved by the authorities. Cermaq’s Freshwater Manager Dusan Munjin told FishfarmingXpert that although it is not a requirement by regulators, pretty much all of the Atlantic salmon smolts entering seawater in British Columbia these days are vaccinated against IHNV (Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus) at a substantial cost to industry. Other industry insiders suggested this cost is artificially high due to the fact that there is only one supplier of this vaccine, which apparently costs about three times as much as the conventional, multivalent vaccine used against some of the commonly encountered bacterial diseases.