A glimpse of the Watermoon

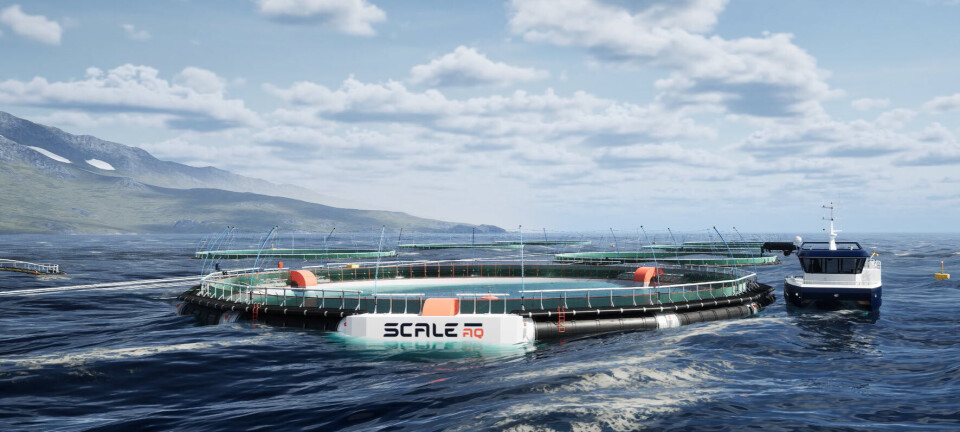

Norwegian fish farmer Eide Fjordbruk wasn't able to share too many details about its new floating closed containment system to invited guests last week but believes the project answers a lot of questions facing the sector

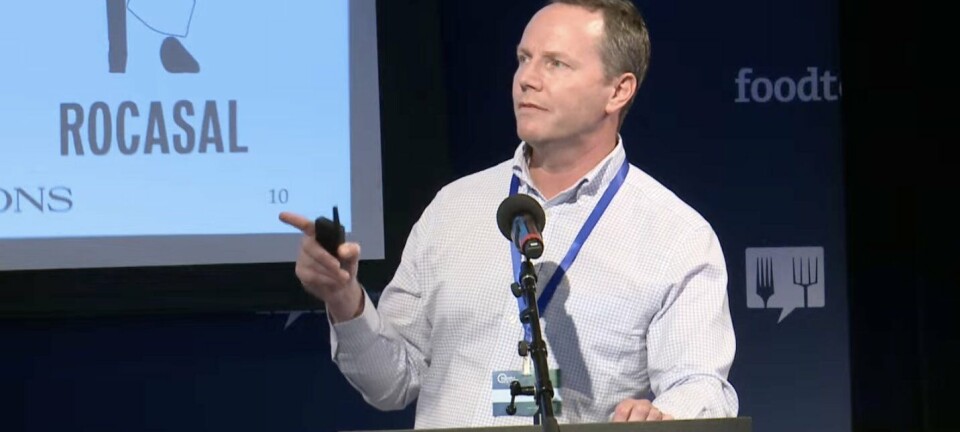

Last Thursday, Norwegian salmon and trout farmer Eide Fjordbruk and the wild fish lobby group Norske Lakseelver (Norwegian Salmon Rivers) invited fish farmers, politicians and researchers to Rosendal on the Hardangerfjord for a conversation about the challenges in the aquaculture industry and the opportunities within closed technology.

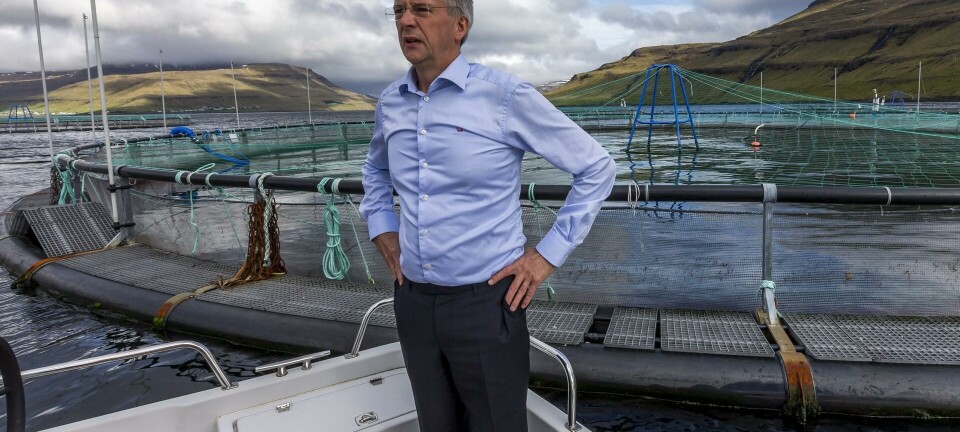

After talks at Eide Fjordbruk’s spectacular Salmon Eye viewing centre, the trip continued by boat towards the company’s major venture, the floating closed containment system “Watermoon”.

On the balcony of the feed barge, we meet project manager Tore Angelskår, who is relatively new to the fish the farming industry. “I don't come from this industry, I come from the oil sector, but Sondre (Eide, the Eide Fjordbruk boss) wasn’t too afraid of that, because they knew the fish part,” he said.

We have considered offshore, we have considered land-based, we have considered various forms of open cages, but what we ended up with was closed technology at sea

New collaborations

The project manager explained that the Watermoon project started with thinking about what Eide’s view was of the future of the farming industry.

“We have considered offshore, we have considered land-based, we have considered various forms of open cages, but what we ended up with was closed technology at sea.”

Angleskår said the technology needed to satisfy everything that Eide wanted did not exist. This led to new collaborations.

“It wasn't just us who had to invent things. Those who were to contribute to realising the project also had to think anew. One of the most important actions we took was to seek those who produce leading supporting technology, such as pumps, and ask if they could contribute their development resources to create a good aquatic environment for the fish in our closed unit,” he explained to Fish Farming Expert’s Norwegian sister site. Kyst.no.

“The development resources in all companies are limited, but our partners contributed specialist expertise in their areas to realise an exciting project and with the hope that there may be business opportunities in an upcoming market.”

Details under wraps

The details of Eide’s closed containment facility remain, for now, on the dark side of the Watermoon. Eide will not yet reveal what material it is built from, as the choice of materials is an ongoing research and development effort. The same also applies to general details of how Watermoon works, as the company is still working on patents and other methods to protect intellectual property rights.

The project first started in a small-scale model in collaboration with the Institute of Marine Research (IMR). From there it was a short step to a full-scale prototype, and at the event, all guests were served a poké bowl with salmon from that prototype.

“We started with an assumption that all our hypotheses were correct. Of course they weren’t. There was a lot that was different. But that’s why we made a small-scale model, to find out. Fortunately, at least our main hypothesis was correct, that this was possible,” said Angleskår.

“When we saw that this worked on a small scale, we pressed the ‘big button’. We were a bit brave then, because we had only had the first exposure in the scale model for about a month. The results from that month were so promising that we immediately began detailed design on the large full-scale unit.”

With just a few sketches and concept images, Eide started the work in January 2022. It took a year of design and calculations, with, according to Angelskår, tens of thousands of hours worked in total. At one point, between 40 and 50 engineers worked simultaneously to reach the finish line, and in December 2022 construction began.

“We are now deploying just under 200,000 individuals who represent a potentially great value and commercial risk for us, so that we can test this device. This is the requirement for us to be able to prove that the device can be used and function on a commercial scale.”

Angelskår said the project is carrying out a trial in collaboration with IMR and with permission from the Norwegian Food Safety Authority for the 200,000 fish. The trial must document that the successful results from small-scale trials are transferable to full-scale operations, and among other things prove that the fish have good wellbeing and welfare.

A collaboration for success

To Kyst.no, the project manager stated that 197,000 fish are now swimming in the Watermoon and will grow up to 5kg. This can take anywhere from 11 to 13 months after insertion. If the test is successful, the next step is to learn from the prototype and design and build the first “proper” version of Watermoon.

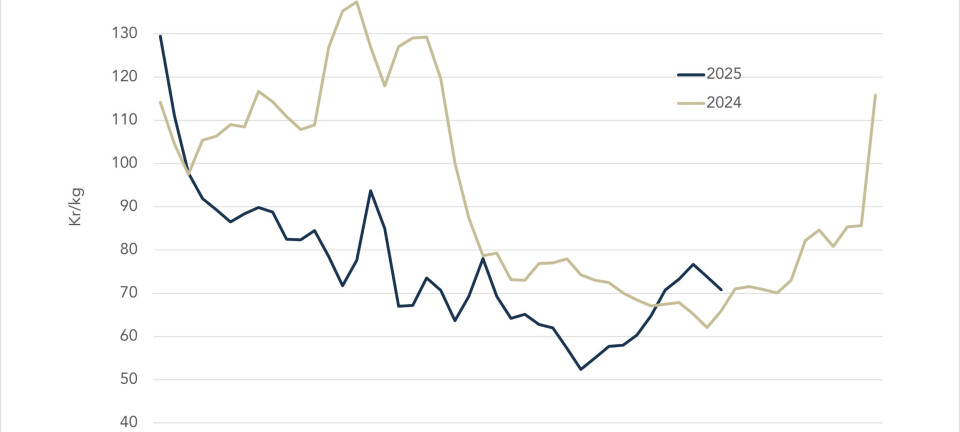

“We are at the beginning of the biological experiment now, and this obviously costs money. We still believe that over time it may become more profitable to continue.”

Angelskår emphasises that if this type of technology is to gain ground and be competitive, its costs and advantages must be recognised and reflected in the permit arrangements by the administration, for example a conversion of one open licence to three closed licences.

“There must be a distinction between those who dare to invest and spend large resources on technology that prevents lice, collects sludge, and improves the fish’s environment, versus those who produce in open traditional cages

“There must be a distinction between those who dare to invest and spend large resources on technology that prevents lice, collects sludge, and improves the fish’s environment, versus those who produce in open traditional cages.”

Sondre Eide has previously compared investment in closed technology in the same way the Norwegian state has invested in electric cars, which became hugely popular thanks partly to tax concessions and free parking, etc.

“A car is obviously faster than a horse, but only if you make arrangements to build roads the car can drive on. In the same way as the electric car scheme, I think it is important to have a good growth course (for closed technology) early on, so that you get as many ‘early adopters’ as possible, so that you are not penalised for being in early. As this gains a foothold and you have achieved a high input, you can combine this with taxes and duties,” Eide said at the time.

Time will tell

Angelskår said: “I believe in the farming industry and I think there will be more such facilities. Whether it will be our facility that succeeds or other types of facility, it’s not important. What is important to us is that many people try. Time will tell who gets it ‘right’, but we have to go through all these ideas to find the best solution out there.”

Sondre Eide is thankful for the support the company have received so far, and at the same time makes an appeal to the authorities.

“It would not have been possible for us to prove fish welfare without collaboration with research institutions such as IMR. Cooperation between business players, R&D, and authorities will, I think, be the key to success going forward, without a doubt,” said Eide.

Exposed locations

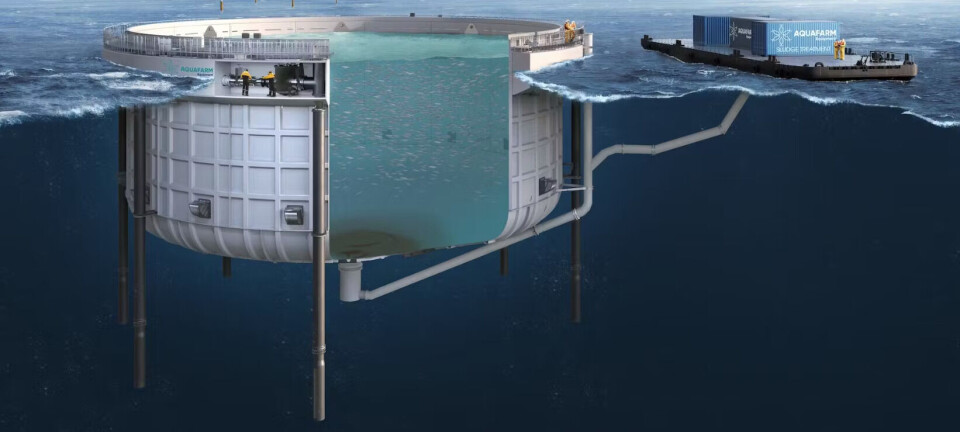

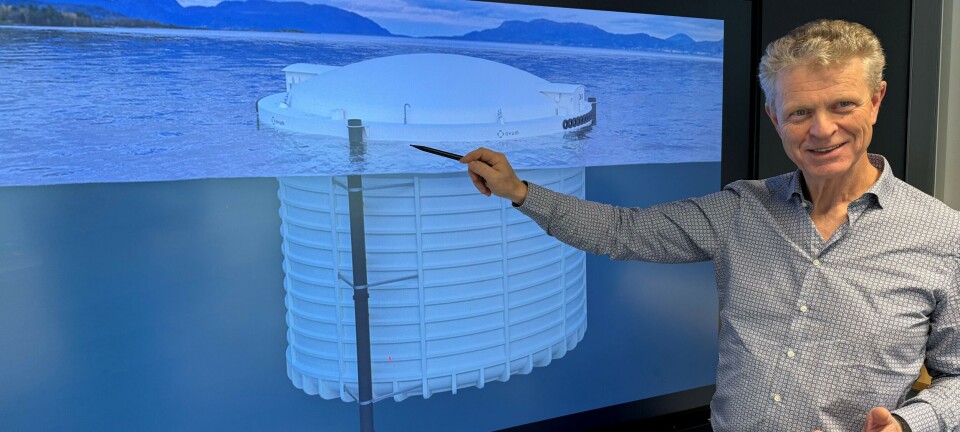

From the surface you don’t see much of the structure, but as with an iceberg, the real size of the structure is below the sea surface. Watermoon has a height of 72 metres. There are several reasons why Eide has chosen to lower the construction below sea level.

“The most demanding area is where sea and air meet. There are waves, ultraviolet light, and other problems. Instead of trying to fight it, we try to avoid it,” said Angelskår.

Most of the structure and the parts of the structure that are most sensitive to these forces are therefore below the sea surface.

Angelskår finally points out that the oil and gas industry has extensive experience with waves, weather, and wind, and Eide should eventually gain that experience with Watermoon.

“One of the basic prerequisites is that this should be able to stand in a fjord, and then we believe that we can stand in a coastal environment, and then we hope that with even more experience and development we can stand in even more exposed locations. But then there will probably be tens of thousands more engineering hours,” he concluded.