These sea temperatures are not suitable for delousing

The technology company OptoScale has analysed data from 308 million fish along the entire Norwegian coast. It has now presented some hard facts for fish farmers as we enter the winter ulcers season.

For the last two or three years, winter seawater temperatures in Scotland have rarely fallen below 7°C, which has caused problems for fish farmers who rely on colder water helps limit one of the industry’s biggest problems, amoebic gill disease (AGD).

But low temperatures also increase the risk of winter ulcers, and that risk can begin from 9°C, according to data collected in Norway by cage camera systems supplier OptoScale.

In the summer of 2023, the company launched a new wound model. Since then, it has registered and classified wounds along the entire Norwegian coast. This data has now been analysed, and the findings may be surprising.

“OptoScale wants breeders to make their decisions based on hard facts, not opinion or trial and error. That's why we took a deep dive into our wound data to investigate whether we could debunk some common aquaculture myths,” OptoScale fish health biologist Ola Brandshaug told Fish Farming Expert’s Norwegian sister site, Kyst.no.

How low can you go?

Myth

1: Safe delousing at 7°C .

Water temperature is of great importance for which delousing method should be used in order to get the gentlest treatment possible. There have been divided opinions about the lowest seawater temperature the fish can tolerate before the risk of ulcer outbreaks increases.

Brandshaug says that many people set a lower limit of 7°C for when it is considered safe to use non-medicinal methods (IMM) for delousing.

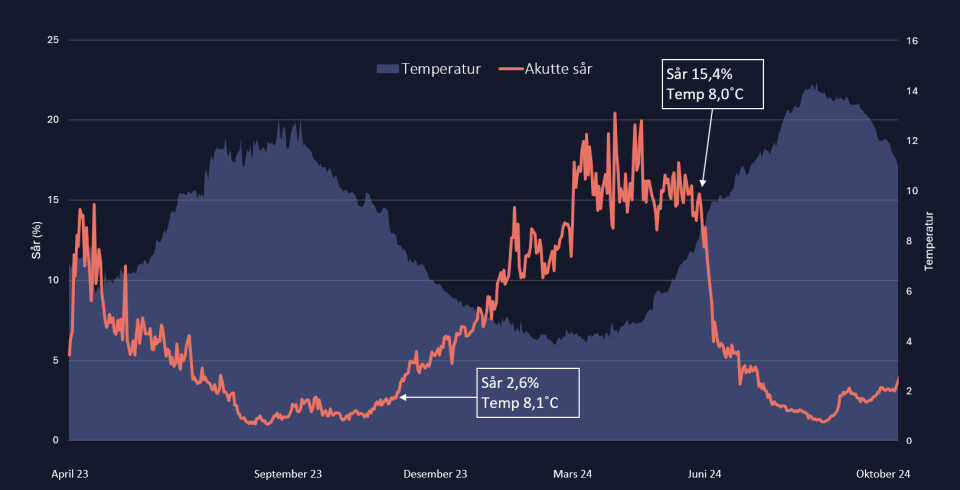

The data that OptoScale has collected shows a clear connection between the proportion of acute wounds and sea temperature. The proportion of acute wounds starts to rise at 9°C towards winter. The level is still low, with 1.3% of fish showing signs of acute ulcers. But that doubles as the temperature drops to 8 degrees, where 2.6% of all fish have acute wounds.

Throughout the winter, the proportion of wounds rises steadily until March, and stabilises between 15% and 20% on average between companies and regions. Late in May, the proportion drops drastically when the temperature rises above 8°C.

“The data show that the risk of ulcers begins to increase at 8°C, not 6°C or 7°C which many relate to today,” Brandshaug states.

The Norwegian Food Safety Authority’s IMM supervisor assesses the risk of treatment as very low at temperatures above 10°C, and very high at temperatures below 5°C.

“It gives a five-degree interval without clear recommendations, although this area should have clearer guidance,” says Brandshaug.

“Although the data show a higher risk of wounds below 8 degrees, the assessment of whether the fish should be treated or not is complex. Water temperature will be one of several factors that must be considered in connection with lice treatment.”

When do the wounds heal?

Myth 2: Little wound healing at low temperatures.

It is well documented that wounds in fish heal more slowly at low temperatures. However, how quickly and how many wounds heal in cold water temperatures is somewhat uncertain.

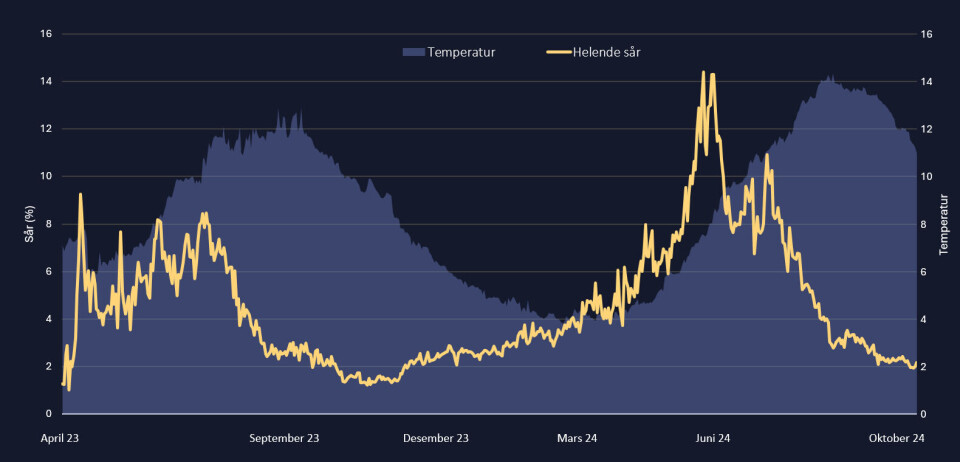

Brandshaug explains that the OptoScale system distinguishes between acute and healing wounds, where the acute ones are open wounds where red musculature is visible, often with swelling around them. Healing wounds are completely or partially covered by white membrane or dark melanin. OptoScale has also investigated how temperature affects wound healing.

“The data show that healing wounds and temperature follow the same trend as acute wounds with a longer peak period between April and mid-July. As the temperature decreases, the proportion of healing wounds gradually increases. This shows that wounds heal even at colder temperatures than expected,” says Brandshaug. “When the temperature rises from around 4 degrees, there is a faster transition from acute to healing wounds. The proportion of healing wounds increases significantly when the temperature exceeds 6 degrees.”

Bigger, not better

Myth 3: Larger fish have fewer wounds.

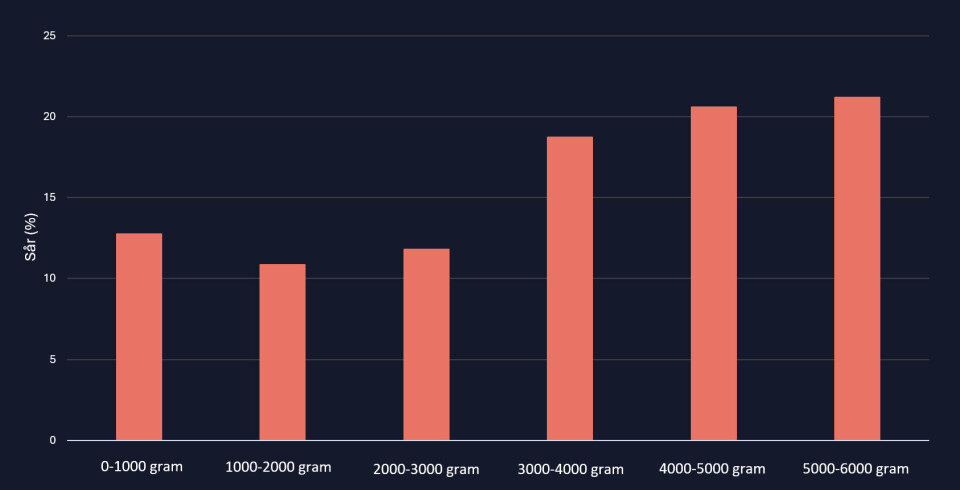

Fish with lower weight in the middle of the production cycle are often handled more than fish approaching harvest. Harvest-ready fish represent a larger investment and are given as much peace as possible to ensure high quality. Therefore, one would assume that fish between 1 and 3 kg have more wounds than fish of harvest size.

“Although fish ready for harvest are given more rest, the trend in our data shows that larger fish have more wounds. This is important when considering allowing the fish to stay longer in the sea to gain extra weight,” says Brandshaug.

He concludes: “308 million fish cannot be wrong - the data give us a clear picture of what is happening below the surface. When the temperature drops, the wound risk increases dramatically, and the limits we thought were safe have to be reassessed.”

OptoScale states that more and more people are using its solutions to increase control in the cages. The technology company continues to analyse data continuously and promises more busted myths in the future.