Chilean MPs to vote on salmon farm sediment law

Chilean politicians will vote this week on legislation that would require salmon farmers to remove sediment from farms.

The proposal includes sanctions ranging from fines to the suspension of aquaculture operations for up to four years for non-compliance.

However, it is expected the proposal will be subject to amendments which can be submitted until tomorrow. The vote in the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Chile’s National Congress, is scheduled for Wednesday.

As it stands, the proposed legislation states that the farm concession holder, or whoever has rights over the farming operation, must remove sedimentary material that has accumulated on the seabed during a fallow period established by Chile’s national fisheries and aquaculture service, Sernapesca.

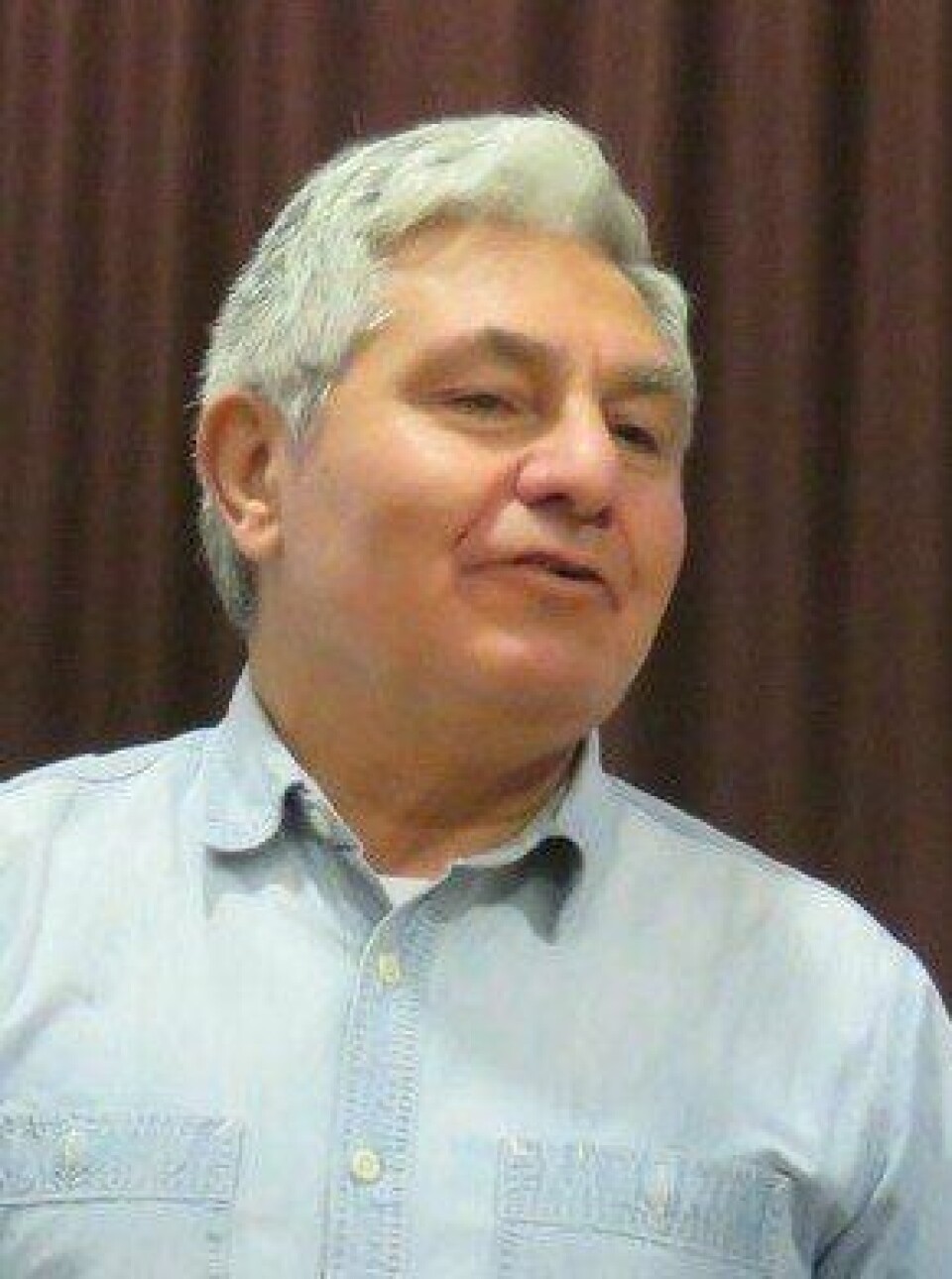

Arturo Clément, president of salmon farmers’ organisation SalmonChile, said that as long as the decision taken by Deputies was based on a technical analysis of what could be achieved with current technology, “we do not have any problem in advancing the initiative”.

“This is a tremendously technical issue, a lot of analysis and there is little research on this. So, we are asking that inquiries are made as much as possible to determine which are the best solutions. As for the position of parliamentarians, some have understood it and others do not have such a clear vision,” Clément said.

Complex issue

“The project talks about sediment removal, and actually we have suggested that this is called sediment recovery. Parliamentarians have a vision that we can go and take out the sludge with a vacuum cleaner, but the issue is much more complex. Our position is supported by several scientists who think the same as SalmonChile. If the sludge is not removed correctly, it is possible to dilute it in the water, being an environmental and sanitary risk.

“What we suggest is that projects be establish that allow us to properly determine and characterise the sludge, so that later we can investigate which are the best ways of remediation. The idea is to find the best available science and if it does not exist, generate it, for the correct use and management of the seabed.”

Already protected

Clément pointed out that the seabed was already protected by the Environmental Information (INFA) rules which involve the sampling and analysis of the condition of water and sediment at farms, with special focus on dissolved oxygen.

If sites are classed as anaerobic they cannot be re-stocked until they have reverted to an aerobic condition.

“Today, more than 20% of INFAs are rejected because aerobic conditions are not present,” said Clément. “Therefore, the authority is measuring, regulation works. There is a control. In spite of this, we do not oppose as a local industry that regulation is improved, but from a scientific point of view, not political.”

The proposed legislation has cross-party support, a rare occurrence in Chilean politics, but that cuts little ice with Clément.

“Well, here they all get political dividends, regardless of the party that they are, of a subject that is tremendously technical,” he says.

Scottish worries

The concern by Chile’s politicians about the effects of fish farm sediment echo those of the Scottish Parliament’s Rural Economy and Connectivity (REC) committee.

One of many recommendations of a recent report resulting from the committee’s inquiry into Scottish salmon farming in the summer is that it is essential that waste collection and removal is given a high priority by the industry, the Scottish Government and relevant agencies.

MSPs said the issue needs to be addressed as a matter of urgency, although the inquiry didn’t investigate how waste collection could be carried out.