Breakthrough possible for Irish aquaculture

Siri Elise Dybdal

The delays in putting in place an adequate response to the ECJ ruling on Natura 2000 by the Irish Government have completely stalled development in the Irish salmon industry for almost seven years, according to the Irish seafood producers’ organisation IFA Aquaculture. In this time, no renewals or new licences have been awarded to the majority of producers. As a result, new techniques have not been trialled, new technologies have not been employed and market share and investment opportunities have been lost, placing the sector at a dangerously uncompetitive position relative to the EU neighbours, IFA Aquaculture claims. As Irish salmon producers cannot compete with the scale of production in countries such as Norway, they have successfully found their own niche in organic salmon, which gains a premium in the marketplace. But, although producers are interested in expanding the production as demand continues to be good, the time it takes to process applications is making this very difficult. Disconnection Catherine McManus, technical manager for Ireland’s biggest salmon producer Marine Harvest Ireland, confirms that the situation has been challenging. “The Irish Aquaculture Industry has stalled in recent years, due primarily to lack of licence renewals and reviews in addition to the lengthy aquaculture licensing process,” she says. “For example, Marine Harvest Ireland applied for a new aquaculture licence in 2011. To date the Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine have not made a determination on this application,” McManus reveals.

IFA Aquaculture executive secretary, Richie Flynn says the problems stem from the extreme difficulties they have had in convincing the Irish Government that they should develop the marine food sector in general, and says the civil service put in charge of the process has had no interest in developing the industry. “It is not just the aquaculture sector, but fishing and processing as well,” says Flynn. “It was a peculiar stance to take at a time when food, which is Ireland’s greatest export, was promoted as the only growth sector in the harsh economic period post 2007. It has been generally acknowledged in Irish society that agriculture and the food sector are the cornerstones that have led to jobs, export and so on,” he says. “But the biggest issue is that there is a big disconnection between policy and service delivery,” he emphasises. “There is no urgency to create jobs or exports. That dysfunction is at the heart of the problem.” For salmon and other species with potential, 600 licences remain on the desk in the department waiting to be processed. In that atmosphere, nobody can make any plans. “It’s hard to tell customers where we are going to be in a year’s time. We know where we want to be, and where we could be if given the opportunity. There is definitely room for expansion in Ireland. In salmon, we have produced 20,000 tonnes before and would have no difficulty at all to do that again. We cannot compete with Norway or Scotland, but we have systems in place for coherent development of the sector,” Flynn underlines.

Frightened According to the IFA spokesman, the massive opposition against salmon farming, particularly driven by those involved with privately owned fisheries, frightens politicians. Although, in general this is extreme behaviour by a small group of people, it is sending a message that they can set the agenda, he claims. However, Flynn says there is also a lot for support for the industry in areas that depend on it for jobs. In 2014, for example, there was some controversy over the use of freshwater to treat AGD on a salmon farm. This led to bad press and publicity generated by a small group of people. “But the ordinary people who lived in the area of the salmon farm gathered a 1000 signature petition saying that they supported the industry and that it was the best use of water and would keep jobs in the area. So it [the bad publicity] is not a reflection of the reality,” Flynn highlights. He believes Ireland is being used by the international angling fraternity – a group of particularly wealthy people opposed to fish farming – as a test bed for what would happen in Norway or Scotland if they could shut the industry down. “It is clearly the agenda. And I know many people in Norway will think they are immune. It is such a big and important industry in Norway that no government in their right mind could ignore them. “But there is a danger in being complacent. We haven’t been. We are fighting the fight on behalf of the international industry,” he says and points out that places in Canada and Ireland are being chipped away at by an international movement that want to get rid of the salmon farming industry. “They want wild salmon maintained for a small number of people,” he claims.

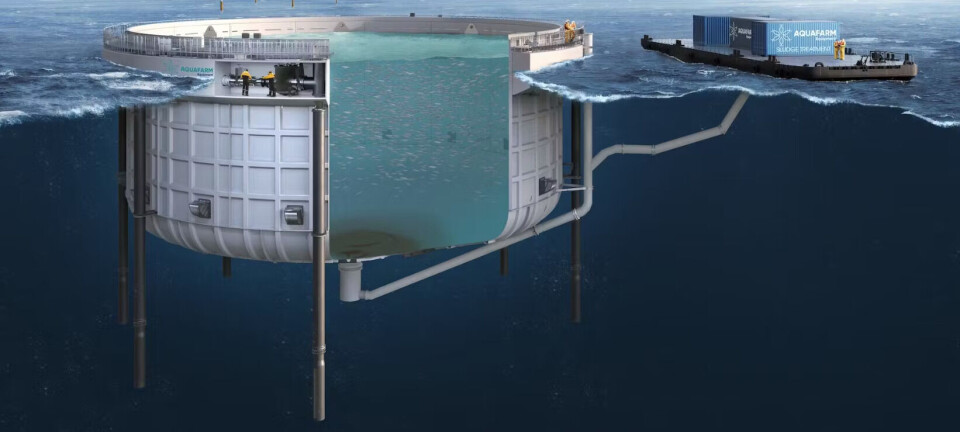

New development programme However, things may be about to change for the better for the Irish salmon farmers. A plan for a new €241 million development programme for the seafood sector, for the period up to 2020, was recently announced in Ireland. The new Programme will be co-funded by the EU through the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and is subject to adoption by the European Commission. Ireland’s Marine Minister, Simon Coveney, is proposing a range of support and development measures under the programme to support the sustainable development of the sector. These include: improving scientific and technical knowledge; providing business, planning and environmental advisory services; increasing training and networking; freeing up capital investment in sites to grow production; a new farmers scheme; increasing organic aquaculture production; and providing stock insurance and aid for harvesting suspensions. He also announced that he would shortly bringing forward a new National Strategic Plan for Aquaculture “that will identify the policy proposals for addressing the many aspects of this industry.” However, Flynn says that this is merely a pipedream unless the people whose job it is to regulate and licence realise that they have an obligation to follow national policy.

Forced to take action Fish Farming Expert spoke to Flynn the day the public consultation on the proposal ended. He says the industry is now hoping the Irish Government’s will prioritise to rapidly make up for lost time and investment. He states that the Minister has recognised “the deep frustration within the sector and by businesses who have been waiting for many years for the system to react to applications for renewals, new sites or adjusted areas.” However, he believes the main reason why there might finally be a push to solve this Irish quandary is the mounting pressure on the Irish Government from Brussels, as the EU holds the purse strings. “Now 60 per cent of the funding for the whole marine industry – and we are talking everything from fishing and navy to research – comes from Brussels. What Brussels have said quite clearly in the last week and a half is that they [the Irish government] will not get a penny of the money unless they sort out aquaculture and aquaculture licencing. It was said in a meeting attended by 40 people. It was very clear that this is a pre-condition for getting any money. So Brussels are back in the driving seat and they are very concerned that the government has been sitting on this problem without doing very basic things,” Flynn reveals. However, he underlines that money is not the only problem: “It requires reorganisation and a little bit of persuasion to break the barriers down. We told them in 2014 and they have had one-and-a-half years to consider. We are just an industry that provides jobs and exports – Brussels holds the purse strings. But this is very encouraging. Watch this space – it is all happening as we speak.” Organic image Despite the challenges the industry has been facing, Flynn says it is important to point out that it still takes its role in the international salmon industry very seriously. “We are very conscious of what is going on internationally and we want to play our part,” he reflects. He says they are adapting new systems with cleaner fish for lice control and have, for example, been involved in the TriNation Pancreas disease work as well as working internationally on gill problems. “Ireland as usual is very open for working with international partners. It is important to show our government that we are part of things internationally,” he emphasises. “On the marketing side, where we farm and the organic image is very important to us. Every country has their advantages and we know what ours are. We still get a better price, but that comes at a cost. It is not just the case of sticking the label organic on it. The feed price is higher and the stocking density is much lower. This is expensive. Anyone thinking it is easy to do organic is wrong – we have been doing it since the early 1990s. You can’t get into it overnight,” Flynn says. Marine Harvest Ireland is one of the companies that have had success with organic salmon for some time. “Organic production is very important for the Irish aquaculture industry. We cannot compete with Norway on scale of salmon production and the cost benefits that scale confers. However, the development of organic aquaculture as our unique selling point fits well with Ireland’s image as a sustainable food producer,” McManus highlights. But she underlines there is room to grow the production: “We have a good customer base for our organic salmon within Europe, Asia, the UAE, Canada and the US with potential for growth. However, the lack of new sustainable licences hampers our ambitions,” she says. If the licencing issue could be resolved, MH Ireland has great plans to develop production further. “Our plan is to double our current production volume with 75% produced as organic Irish salmon and remainder produced as premium Irish salmon,” she says. Flynn sums up what needs to be done for the next period to be more progressive for the industry. “We need clear commitments in the annual report to the European Commission to eliminating the backlog of licence applications within a very tight timeframe and continued assistance with identification of new sites as well as better or more efficient uses of existing sites,” he concludes.