Taking the plunge: a submersible salmon cage designed for Scotland

Salmon farmers in Scotland and Ireland are being invited to work with a start-up company, Impact9, on a new submersible cage concept that offers affordable access to high-energy sites in the region’s relatively shallow waters.

Dublin-based engineer John Fitzgerald, who founded Impact9, has used his background in marine energy to design and apply to patent a radically different pen that uses elastic properties to give it unique compliance to waves.

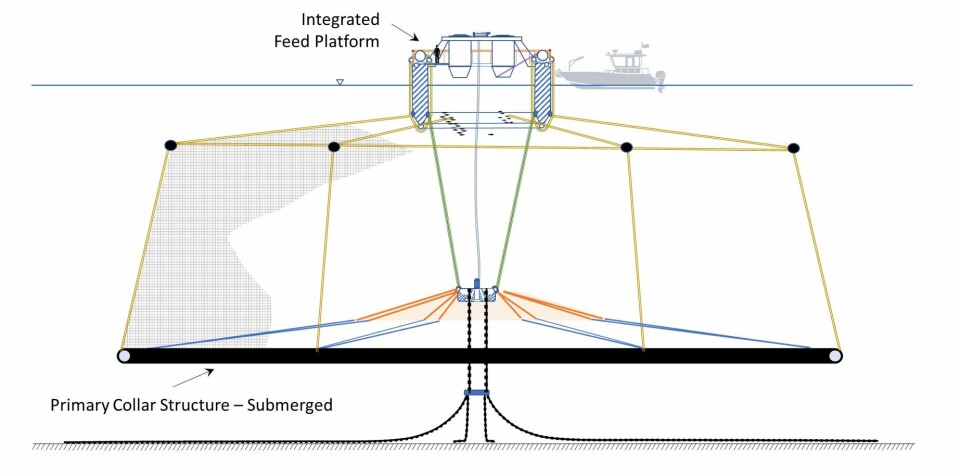

Impact9’s cage concept is based around a central, strong backbone structure, which is centrally moored with a single-point mooring. It will provide a safe working platform and a home for feed and farming equipment.

Inflatable collar

Each net is suspended from the backbone and includes an inflatable collar near the base.

The cage would alleviate lice and algal bloom problems by keeping salmon six metres below the surface – or more if required – and is designed to be used in the 30-40 metre depths common around the British Isles.

Fitzgerald has a lot of expertise in wave energy, having worked for Wave Energy Scotland on Checkmate’s Anaconda Eave Energy Converter and on the Archimedes Waveswing wave energy device, among other projects.

Cost-competitive

He was drawn to the sector after seeing details of Norwegian innovations such as SalMar’s Ocean Farm 1, although Impact9’s concept would be much cheaper.

“About a year ago I started to formulate ideas about how better to contain fish in a way that we could take operations further offshore in a way that wouldn’t cost [much more] in terms of capital costs and operational costs,” said Fitzgerald.

“We were really focused on keeping those elements competitive relative to conventional fish farming as much as possible. We wanted to get out there with costs that were going to be far more competitive than the kinds of proposals that were coming into Norway.

Operational flexibility

“We can adapt HDPE collars into this structure but there’s some very good operational innovations that can be done with inflatable beam collars, so we’re looking at that to see how we can actually bring nets out and literally inflate them, pressurise them so that they grow out into their containment position around the central structure.

“That allows a lot of operational flexibility as well.

“There’s a lot of innovation there, and the outcome of all that is inexpensive access to offshore zones, a lot less operational cost on divers, less dependence on wellboats, and - because of the submerged position - resistance to lice and potentially algal blooms as well.”

The wave compliance of Impact9’s cage has been tank tested at the LiR National Ocean Test Facility at Ringaskiddy in Cork, and numerical modelling using Proteus DS software has also been carried out.

“There’s an independent engineering study being done by Dublin Offshore Consultants to look at the cost metrics and validate some of those aspects, and that’s just being completed in the next week or two,” said Fitzgerald.

The aquaculture accelerator programme, Hatch, has already shown faith in the concept by including Impact9 in its third cohort of start-ups undergoing an intense three-month course to ready them for further growth.

Shallower water

Fitzgerald, who is currently on the Hatch programme in Hawaii, points out that most current submersible cages, such as those used to farm kampachi there, are for deeper water than that available to Scottish and Irish fish farmers.

“We’re cognisant that a lot of farmers in Scotland will be looking to go to exposed parts of bays, say like The Minch, outer parts of lochs where production licences will be more readily available, but where they may currently be a bit reluctant to go with the available technology,” he said.

“Water depth in those areas is typically 30-40 metres, not the 60-100 metres you’d have off Hawaii and in Norway. We were very clear that we wanted to solve that for that kind of shallower water depth problem.”

Honing the technology

Impact9’s cage is still at the concept stage and is open to change, but Fitzgerald hopes things can move quickly.

“The phase we’re in now, we want to work with the industry, with producers,” he said.

“We’re well aware that there’s going to be a lot of different demands out there and we want to try and hone the technology, so we’ll be putting the ideas out to try and engage the sector to hone the solution and really work fast to fix a design and prototype and demonstration phase and raise funding to bring it into a kind of demonstration project.

Marine qualification

“One of the things we’ve learned a lot from in marine energy is how to go through marine qualification – test plans, looking at what standards apply, what sequence of testing is sensible, how can we validate this in the eyes of the market, both regulatory-wise and in terms of meeting customer requirements.

“So, we’ll be setting up a qualification programme costing that out and raising money to try and bring this through. There’s a lot of goodwill in the various state agencies in Scotland, Ireland and at European level in the blue growth sector. It’s an exciting space – a lot of people want to solve this problem and I do get an impression that we can really push it forward, so that’s what we’re going to try and do.”