Aboriginally-owned tank farm for salmon set to open

Opinion

The land-based fish farm, set on a reserve belonging to the ‘Namgis First Nation whose traditional territory is located around the Nimpkish River just south of Port McNeill on the northern tip of Vancouver Island, is one of a number of units envisioned to produce a steady supply of high quality Atlantic salmon at a market price considerably higher than that paid for conventionally farmed salmon in the North American market. A number of financial estimates have been obtained based on experiments conducted at The Conservation Fund’s Freshwater Institute in West Virginia, and some of them- like production time, selling price and cost of processing- may not be realistic.

The ‘Namgis First Nation along with its long-term Chief Bill Cranmer has been a vocal opponent of conventional salmon farming in the area between the Nimpkish River and the B.C. Mainland- an area commonly referred to as the Broughton Archipelago. But this opposition has largely been based on unsubstantiated assertions and reports provided by the self-declared “researcher” Alexandra Morton, whose reputation and questionable credibility was severely damaged during a recent investigation into a low return of salmon to the Fraser River in 2009 (which was followed by a record run the next year). Claims such as the ever-recurring one about clams around salmon farms turning “dark and smelly” have been quashed by experienced diggers who say that if you don’t harvest the clams regularly, they will turn dark and smelly. Harvest of clams is prohibited near salmon farms, and that’s why some of them turn that way after a number of years of not being harvested/turned over.

The ‘Namgis First Nation and its project management have been very good at providing regular updates about the initiative, and Judith Lavoie of the Times Colonist recently provided some information on the project and the anticipation of more information coming from the initiative, which is a few months behind schedule according to previous schedules;

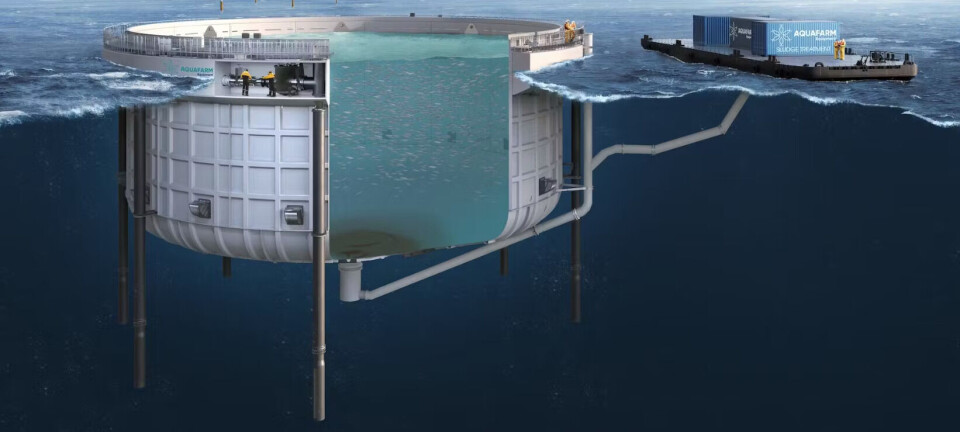

The People of the Salmon are preparing to show there is a different way to farm fish — and that it can make money without hurting the environment. ‘Namgis First Nation, whose 4,000-year-old traditions are tied to the Pacific salmon of the Nimpkish River, is about to open the first phase of a unique $8.5-million (~€ 6.3 million) closed-containment Atlantic salmon farm on reserve land south of Port McNeill. The aim is to prove it is economically viable to raise Atlantic salmon on a commercial scale in tanks on land, rather than in open net pens in the ocean. The project is being watched intently by the salmon-farming industry and conservation groups.

The facility will be the first commercial-scale, land-based Atlantic salmon farm in Canada, although there is a small pilot project in West Virginia. Jackie Hildering, community liaison for Save Our Salmon, said a blessing ceremony is set for Feb. 18 and delivery of 23,000 Atlantic salmon smolts is expected in March. “The aim is to show there’s a better way,” she said. The ‘Namgis have seen open-net-pen fish farms proliferate in the Broughton Archipelago and believe diseases and pollution from the farms are killing wild runs of salmon. Finding alternatives to ocean farms is becoming increasingly important with confirmation of Infectious Salmon Anemia outbreaks on East Coast farms, Hildering said.

‘Namgis Chief Bill Cranmer is convinced ocean-based fish farms hurt wild fish. He’s equally sure the closed-containment project will be successful. “The [farms] are so much a danger to our wild stocks. It affects the herring and everything else around the area. The clams are not healthy. They are a dark colour and smell because of the excrement,” he said. The K’udas project — whose name means place of salmon — could ultimately produce 2,500 tonnes of fish a year, but the initial phase will produce about 470 tonnes. “I am hoping we can move those farms out of the ocean,” Cranmer said. “The big fish-farm operations say it will cost too much, but from our calculations, it’s going to be a good business and it’s going to be environmentally friendly.”

The land-based farm is entirely owned by the ‘Namgis, but funding has also come from the federal government, Tides Canada and conservation and philanthropic organizations. The fish will be grown in five 500-cubic-metre tanks using recirculated fresh water and will be ready for harvest in 12 to 15 months. In open-net pens, the fish take 18 to 24 months to grow to harvestable size. “We can control all the variables. There are no predators and we control swim speeds. Happy fish grow faster,” Hildering said.

The flavour is also likely to be good, according to Albion Fisheries, the wholesale company that has a contract with K’udas. Steve Hughes, Albion general manager, noted the company already buys from West Virginia and the fish sell for a premium price. “It tastes better — the fat content is quite high, so it has a lot of flavour.”

The 100-gram starter fish are coming from Marine Harvest, the largest Atlantic salmon-farming company in B.C. Other companies will be watching to see how the project progresses, said Mary Ellen Walling, executive director of the B.C. Salmon Farmers Association. “It’s pretty exciting,” she said. “We are looking forward to seeing a full cost analysis and getting a good understanding of the capital costs. That will be very important.” Health of the fish through the growth cycle will also be watched, Walling said. “The companies are very interested to see if they can produce large-scale volumes.”