Chicken feather-oil 'can improve fish survival'

University researchers in the United States are using a feather-conditioning oil that comes from a gland on chickens' tails to improve survival at fish farms.

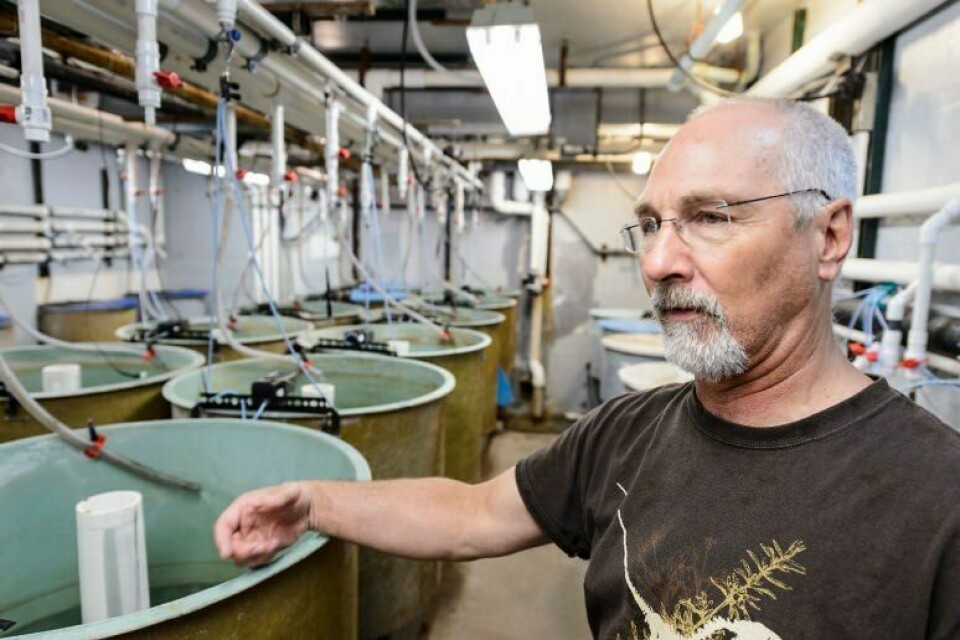

University of Wisconsin-Madison animal science professor Mark Cook was exploring underused products from animal agriculture. Curious about the preen gland, he and postdoctoral researcher Jake Olson noticed that the gland secreted an anti-inflammatory compound. Aware that a previous test had shown that a different anti-inflammatory had accelerated fish growth, Cook and Olson contacted Terry Barry, a university expert in aquaculture.

“We did a quick study with fathead minnows, and they had better growth and survival,” says Barry, who is an expert on fish stress responses. “But when we tried rainbow trout and yellow perch, we did not see the growth acceleration.”

But they did see a surprising positive effect.

“Every time they got stressed because the oxygen level had dropped or water temperature suddenly changed, fish fed a derivative of the preen-gland oil survived, but the others did not,” Barry said.

Researchers believe the oil allows fish to focus energy that's otherwise spent fighting off infections and parasites in their gut, improving their chances of survival in stressful situations.

Global impact

The oil, which they've named cosajaba - pronounced “co-SA-juh-buh” - could have a global impact on the Atlantic salmon industry, Barry said. The industry loses millions of pounds' worth of fish when they're moved between tanks, vaccinated and transition from fresh water to saltwater.

“Mark Cook, being a world-renowned poultry expert, had been interested in this for a long time,” said Olson. “He finally got the chance when I came to his lab in 2011, looking to study the effects of lipids on immune function, particularly through diet. Fish get stressors that you never see in terrestrial animals. The oxygen content in water can dramatically fluctuate. In aquaculture, there is stress from handling and vaccination.”

In experiments that compare fish feed with and without cosajaba, “We are measuring growth, changes in body condition, immune markers, and stress markers that follow acute stress,” said Olson, “and we plan to look at clearance of those stress hormones.”

Stress response

Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) filed a patent on the preen oil discovery in February, and last year, Cook, Barry and Olson applied funding from WARF’s Accelerator program to explore the business implications of the improved survival.

The researchers have focused on how unusual fatty acids in cosajaba oil dampen the stress response, and other questions need answered before the researchers start a spin-off company, said Barry. “How long do we need to feed the oil, and when do we need to start? Can we mass produce cosajaba oil? Can we find a faster way to test effectiveness than feeding fish and measuring stress?”

In the US, the preen gland is discarded as waste from about nine billion broiler chickens slaughtered each year.