Aquaculture and Fisheries – the Big Picture

Odd Grydeland odd@fishfarmingxpert.com

A parallel report was recently published by the Washington, DC-based World Resources Institute, and both of these documents provide similar information and recommendations. Some of the highlights of the reports include: • Fish now accounts for about 17 per cent of the global population’s intake of animal protein (over 50% in some countries), and a growing middle class can afford to buy more seafood • The global supply of wild-caught fish has peaked some time ago, so any future increase in world fish consumption will need to come from aquaculture • To meet this anticipated demand, world aquaculture production needs to more than double over the next 35 years or so- from its current level of about 67 million tonnes (MT) to some 140 MT by 2050 • Asia represents about 88 per cent of total output from the aquaculture sector in the world (excluding marine plants and non-food products), while Europe only produces less than 5% • The health benefits of eating fish- especially oily fish like salmon- are confirmed • Technological innovation and adoption- along with other measures- have worked to improve aquaculture’s productivity and environmental performance in recent decades Total world fisheries and aquaculture production (million tonnes- excluding marine plants): Most of the data from the FAO report only cover the period up to and including the year 2012, but some information for 2013 is also provided.

The United Nations expects that the world population will grow by another 2 billion by 2050- to about 9.6 billion. And already, more than 800 million people continue to suffer from chronic malnourishment. The challenge is then how to feed our planet while at the same time safeguarding its natural resources for future generations. The FAO report points out that “Never before have people consumed so much fish or depended so greatly on the sector for their well-being. Fish is extremely nutritious – a vital source of protein and essential nutrients, especially for many poorer members of our global community. Fisheries and aquaculture is a source not just of health but also of wealth “.

This now famous graph shows the levelling off of the capture fishery production since the late 1980’s, and the steady growth of the world aquaculture production. China has been responsible for most of the growth in fish availability, particularly from its inland aquaculture industry. Also, in 2012 China produced almost 2.3 million tonnes of fish from its inland capture fishery, and in the same year Norway’s total aquaculture output was slightly less at 2.15 million tonnes. Fish consumption in China has also increased dramatically along with its increasingly affluent middle class- by some 6 per cent annually between 1990 and 2010 to over 35 kg per person per year, compared with about 15.4 kg in the rest of the world. China is also the largest exporter of fish and fishery products by far, but the country has also (since 2011) become the world’s third largest importing country, after the United States and Japan. The European Union is the largest market for imported fish and fishery products, and its dependence on imports is growing. Europe only produced 4.3% of world aquaculture output in 2012, down from 12.3% in 1990. The global trend of aquaculture development gaining importance in total fish supply has remained uninterrupted. Farmed food fish contributed a record 42.2 percent of the total 158 million tonnes of fish produced by capture fisheries (including for non-food uses) and aquaculture in 2012. This compares with just 13.4 percent in 1990 and 25.7 percent in 2000. Asia as a whole has been producing more farmed fish than wild catch since 2008, and its aquaculture share in total production reached 54 percent in 2012, with Europe at 18 percent and other continents at less than 15 percent.

The record production of seafood from aquaculture in 2012 was also supplemented with the output of some 23.8 million tonnes of aquatic algae, bringing the total figure of aquaculture production that year to over 90 million tonnes- very close to the 91.3 million tonnes of fish from capture fisheries. The estimates for 2013 aquaculture production are for 70.5 million tonnes of fish and 26.1 million tonnes of aquatic algae/seaweed. The world-wide production of food fish from aquaculture expanded at an annual rate of 9.5 per cent between 1990 and 2000, and by 6.2 per cent in the period 2000 to 2012, when it more than doubled (from 32.4 MT to 66.6 MT). In North America however, aquaculture production was lower in 2012 than in year 2000.

FAO says in its 2014 report that at the time of writing, some countries (including major producers such as China and the Philippines) had released their provisional or final official aquaculture statistics for 2013. According to the latest information, FAO estimates that world food fish aquaculture production rose by 5.8 percent to 70.5 million tonnes in 2013, with production of farmed aquatic plants (including mostly seaweeds) being estimated at 26.1 million tonnes- more than double that produced in 2000. In 2013, China alone produced 43.5 million tonnes of food fish and 13.5 million tonnes of aquatic algae. In 2012, about 18.9 million people were engaged in fish farming- more than 96 per cent of those were in Asia. Overall, the FAO estimates that fisheries and aquaculture provide the livelihoods of 10-12% of the world’s population. Unfortunately, many fish stocks around the world are harvested at rates deemed to be unsustainable. The proportion of assessed marine fish stocks fished within biologically sustainable levels declined from 90 per cent in 1974 to 71.2 per cent in 2011, when 28.8 per cent of fish stocks were estimated as fished at a biologically unsustainable level and, therefore, overfished. The FAO report suggests that rebuilding overfished stocks could increase production by 16.5 million tonnes worth about US$ 32 billion (€ 23.5 billion).

Illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing also remains one of the greatest threats to marine ecosystems says the report, undermining national and regional efforts to mange fisheries sustainably and conserve marine biodiversity. “Fisheries resources available to bona fide fisheries are poached in a ruthless manner by IUU fishing, often leading to the collapse of local fisheries and threatening the livelihoods of fishers and other fishery-sector stakeholders and it also exacerbates poverty and food insecurity”. Rough estimates indicates that IUU fishing takes 11-26 million tonnes of fish each year, for an estimated value of US$ 10-23 billion (~€ 7-17 billion). As well, bycatch and discards remain a major concern, and the FAO has developed international guidelines on bycatch management and discard reduction.

The proportion of fisheries production used for direct human consumption increased from about 71 per cent in the 1980’s to more than 86 per cent (136 million tonnes) in 2012, with the remainder (21.7 million tonnes) destined for non-food uses such as fishmeal (mainly for high-protein feed) and fish oil (as a feed ingredient in aquaculture and also for human consumption for health reasons). The proportion of world fisheries that is processed into meal and oil is significant, but declining, and more and more fish meal is now produced from fish remains or other fish by-products. In 2012, about 35 per cent of all fishmeal production was obtained from such fish residues.

In 2012, global production of non-fed species from aquaculture was 20.5 million tonnes, including 7.1 million tonnes of filter-feeding carps and 13.4 million tonnes of bivalves and other species. Continuing its established trend, the share of non-fed species in total farmed food fish production declined further from 33.5 percent in 2010 to 30.8 percent in 2012, reflecting a relatively stronger growth in the farming of fed species.

FAO reports a good overall status of governance in aquaculture, according to a recent survey. The “ecosystem approach to aquaculture” (EAA) and spatial planning are becoming important in supporting the implementation of the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, which was established back in 1995, and expanded to include aquaculture production. There is also an increasing interest in the certification of aquaculture production systems, practices, processes and products. “However, the plethora of international and national certification schemes and accreditation bodies has led to some confusion and unnecessary costs. In this regard, FAO has developed technical guidelines on aquaculture certification and an evaluation framework for assessing such schemes. Overall, the major challenge for aquaculture governance is to ensure that the right measures are in place to guarantee environmental sustainability without destroying entrepreneurial initiative and social harmony”.

The organization says in its report that a good example of certification in aquaculture is the application of the Global Aquaculture Alliance’s Best Aquaculture Practices to certified processing plants all over the world such as in Australia, Bangladesh, Belize, Canada, Chile, China, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Norway, Thailand, the United States of America, and Viet Nam. “The aim is to prove to the public that aquaculture production systems and processes are not sources of pollution, disease vehicles, threats to the environment or socially irresponsible”. A number of salmon farming companies have now also obtained certification for their fish farms, and fish feed manufacturers have done the same for their plants.

The farming of tilapias, including Nile tilapia and some other cichlids species, is the most widespread type of aquaculture in the world. FAO has recorded farmed tilapia production statistics for 135 countries and territories on all continents. The true number of producer countries is higher because commercially farmed tilapias are yet to be reflected separately in national statistics in Canada and some European countries. The growth in aquaculture production around the world is highly variable, with Africa leading the way and North America falling behind.

The number of people engaged with aquaculture around the world has increased from about 8,000 to almost 19,000 over the past twenty years. In Norway there are some 5,900 persons working in the fish farming industry compared with about 4,600 in 1995, while the fishing fleet has been reduced to half of what it used to be (12,000 in 2012 compared with 24,000 in 1995). Another interesting statistics from the FAO report is the productivity development of fish farmers in different regions, which in 2012 ranged between 3.2 tonnes per person per year in Asia and a high of 59.3 tonnes per worker in North America.

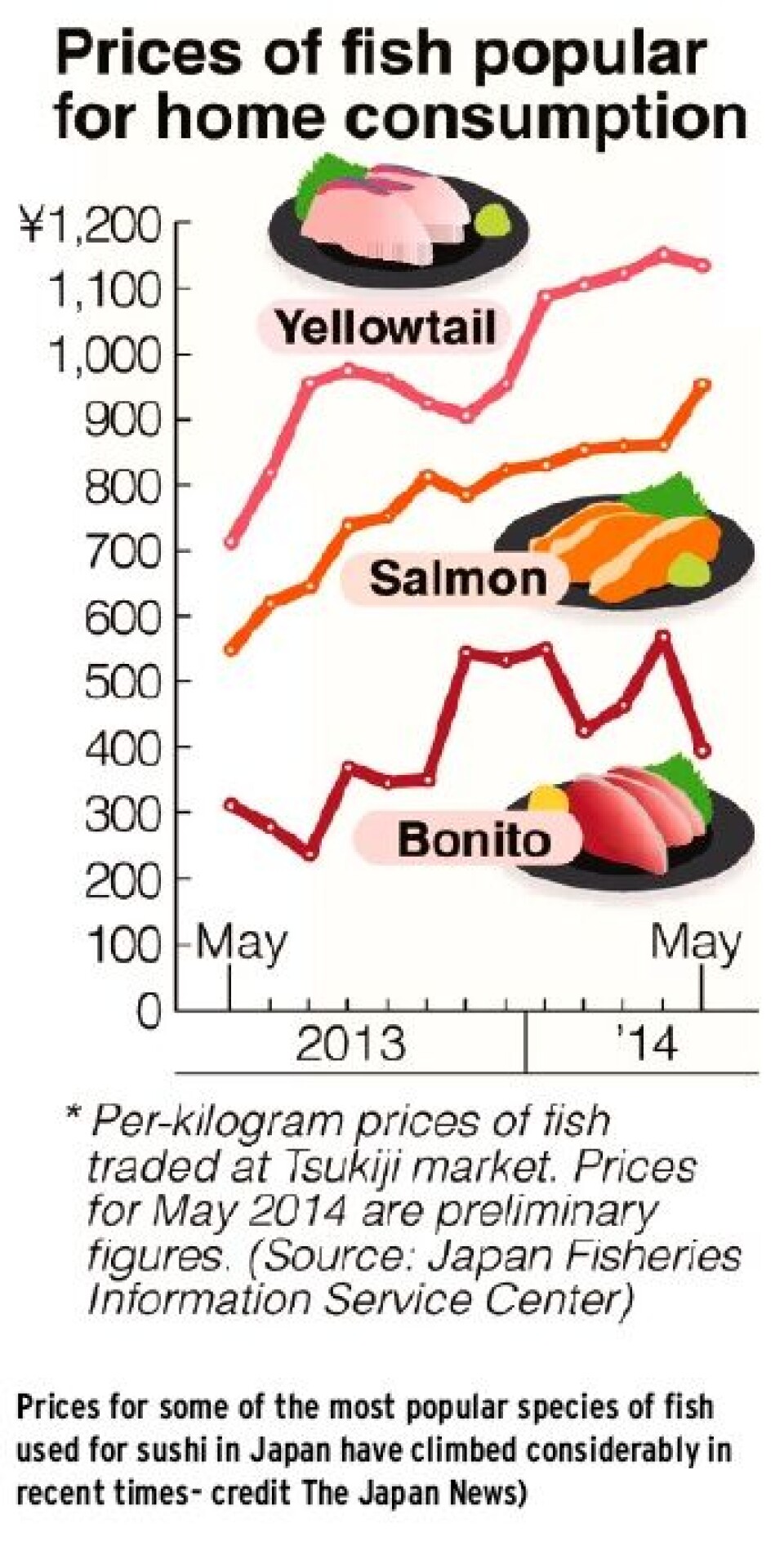

When it comes to the outlook for fish prices, the future looks positive, says the FAO report; “..preliminary estimates for 2013 point to a new increase in trade of fish and fishery products. Exports reached a new record of more than US$136 billion, up more than 5 percent on the previous year. For major developed countries, still suffering from economic slowdown or only slowly recovering, this increase in trade value is mainly a reflection of inadequate supply pushing prices upwards. Despite the instability experienced in 2012 and part of 2013, the long-term trend for fish trade remains positive. Thanks to their slow but continuing economic recovery, major developed economies are expected to revitalize consumer interest in seafood. Demand is also increasing steadily in emerging economies for high-value species such as salmon, tuna, bivalves and shrimp. However, with capture production stable and various factors restricting aquaculture supply of shrimp and salmon – two of the world’s major traded species – the upward pressure exerted on prices by continued global demand growth may be significant. Aquaculture has benefited to a greater degree from cost reductions through productivity gains and economies of scale, but it has recently been experiencing higher costs, in particular for feeds, which has affected production of carnivorous species in particular. Aquaculture production also responds to price changes with a time lag, given the stocking and production cycle for most species. In recent decades, the growth in aquaculture production has contributed significantly to increased consumption and commercialization of species that were once primarily wild caught, with a consequent price decrease. This was particularly evident in the 1990s and early 2000s with average unit values of aquaculture production and trade in real terms (2005 value) regularly declining. Subsequently, owing to increased costs and continuous high demand, prices have started to rise again. In the next decade, with aquaculture accounting for a much larger share of total fish supply, the price swings of aquaculture products could have a significant impact on price formation in the sector overall, possibly leading to more volatility”.