Get on board the gill health awareness train

It's never to early in the season to put nature's challenges under the microscope, says Hamish Rodger, chief fish health officer for diagnostics and analysis company Patogen

In the song words of Curtis Mayfield, “People get ready, there’s a train a-coming…” and what we’re talking about are the coming gill health challenges in salmon and trout sea sites which will soon be upon us. But is it too early to be talking about gill health? In brief; no. It is never too early. Here is why:

The gills of recent post smolts transferred to sea are delicate, naïve, and still adapting to the marine environment, and some strains of fish are more robust than others.

- Sea water temperatures are rising, and the natural spring coastal phytoplankton bloom normally peaks in late April (in Norway) although this has been occurring later in the past 15 years. The offshore phytoplankton bloom will occur about one month later and although the majority of the species in these blooms are not harmful, some may be. Following these there will be a natural zooplankton bloom, again many of which are not harmful, however, as we know from 2023, some gelatinous species can cause significant gill and skin damage.

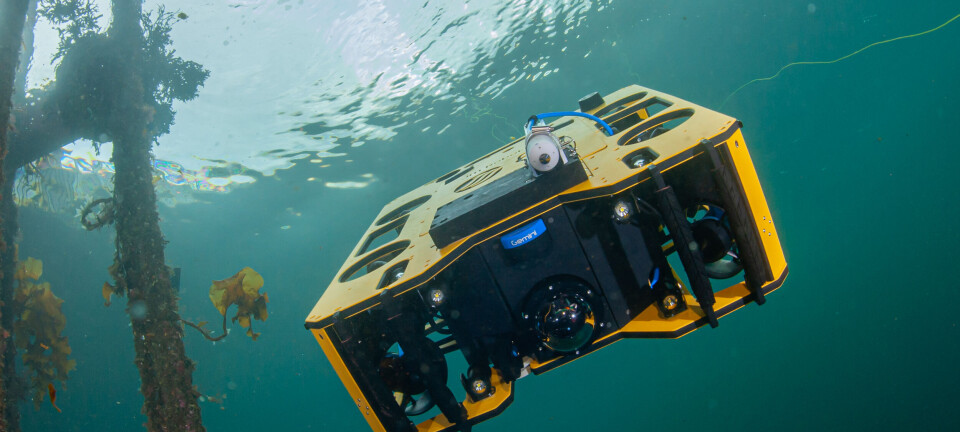

- Biofouling on nets is starting to grow now and net cleaning will be required regularly. There is increasing evidence that the detritus from the cleaning process will induce a low level of gill pathology (usually small gill aneurysms) which will repair given good water quality. However, if there are repeated insults to the gills then these lesions will accumulate.

We now know that amoebic gill disease can cause clinical disease even at sea temperatures of 7°C.

Hamish Rodger

- The gill amoebae (perurans, or ‘the persevering one’!) can form pseudocysts off the fish and then becomes active again when conditions are optimal for them. The triggers for this will be temperature and food (bacteria), and we now know that amoebic gill disease (AGD) can cause clinical disease even at sea temperatures of 7°C.

- In addition, other gill pathogens such as the bacteria Ca. Branchiomonas cysticola increase in quantity on gills after thermal delousing and are a suspected contributor to complex gill disease (CGD).

- Higher levels of the parasite Paranucleospora

theridion (syn. Desmozoon lepeophtheirii) are also found in CGD.

There is increasing evidence at both farm and laboratory level that these and two other pathogens also contribute to gill disease by themselves and, in some cases, are contributors to CGD. These are namely:

- salmon gill pox virus (SGPV) which will induce

stress-related gill disease,

- Tenacibaculum maritimum which often multiplies on damaged gill surfaces and due to toxins can have a lethal systemic impact on the fish.

The more of these pathogens the gills have, and the higher the quantity of each, the more at risk the fish are of developing significant gill disease. With the knowledge of the presence (or absence) and quantity, of each pathogen then decisions can be made and strategies put in place to reduce the impacts on infected, as well as naïve, fish. These may include freshwater baths, alternating net cleaning frequency or method, changes in feeding practice and alternating treatment options.

So, what can you do?

1. Monitor water samples regularly for plankton species and number (we can show you how to do this) and do not put fish to sea if harmful species are present and do not bath treat fish with such seawater.

2. Check gills for gross gill scores regularly and take gill smears for fresh on-site microscopy if you observe any pale patches (we can help here as well).

3. Sample gills for histology at least once a month and before any proposed bath treatment and adjust treatment plans based on findings.

4. Sample gills for the 4 (or 5) pathogens on at least a monthly basis in each site to monitor presence and quantity to enable planning and preparation for freshwater bath treatments.

Forewarned is forearmed, so people get ready.