Farms aren’t to blame for blooms

An unusually large bloom of toxic algae has resulted in fish kills in BC, causing activists to point fingers at salmon farmers, despite the fact that scientists say it’s a natural event.

Two farms operated by Cermaq Canada have been hit hard by a type of toxic algae called Chrysochromulina.

The farms are located on the West Coast of Vancouver Island, at the Ross Passage and Millar Channel, in the Clayquot Sound. Since the end of May, losses have been significant – with mortality reaching 10% at the worst affected site.

Scapegoat sought

Some NGOs have started pointing the finger at salmon farms as the cause of these HABs but, according to scientists, aquaculture is not the smoking gun.

Indeed, Fish Farming Expert spoke with the Program Manager at the Harmful Algae Monitoring Program at Vancouver Island University, Nicky Haigh, who explained: “All research that has been done on this question indicates that any nutrient signal from farms disappears within 100m of the farm site.”

“The deep water sites typical of BC salmon farms mean that there is a high dilution effect – and in addition the west coast is an upwelling zone, meaning there are naturally high nutrient levels, so the input from salmon farms is insignificant,” she added.

Haigh explained that farms are not making HABs worse – the blooms are a natural phenomenon that have been documented prior to the arrival of salmon farming in BC.

“These blooms are natural events that appear to have been occurring in BC before salmon farms arrived in the late 1970s. The blooms do not originate at the salmon farm sites – rather they may come from seed areas in sheltered bays or larger offshore blooms, and move into the sites with currents or tidal flow,” she explained.

Last year, the “blob” of warm water off the coast of BC contributed to an usual giant bloom of Pseudo-nitzchia which was present for most of the summer – and it seems that HABs are increasing in frequency.

“Certainly it appears that HABs are increasing world-wide”, said Haigh. “In many cases this has been linked to increased anthropogenic nutrient inputs, and perhaps to climate change”.

Already this year, temperature monitoring of the waters surrounding Vancouver Island have indicated a 2-degree increase over previous years.

“We have always had HABs in BC,” said Haigh, “this latest occurrence in Clayoquot Sound is not the first fish-killing Chrysochromulina bloom we have seen. In the 18 years we have been running the Harmful Algae Monitoring Program (HAMP), we have gained a great deal of knowledge on fish-killing HABs in our region. We have been able to identify many of the different fish-killing algae species in BC – and this knowledge could also be of benefit to assessment of HAB impacts on wild fish stocks.”

Deep concerns

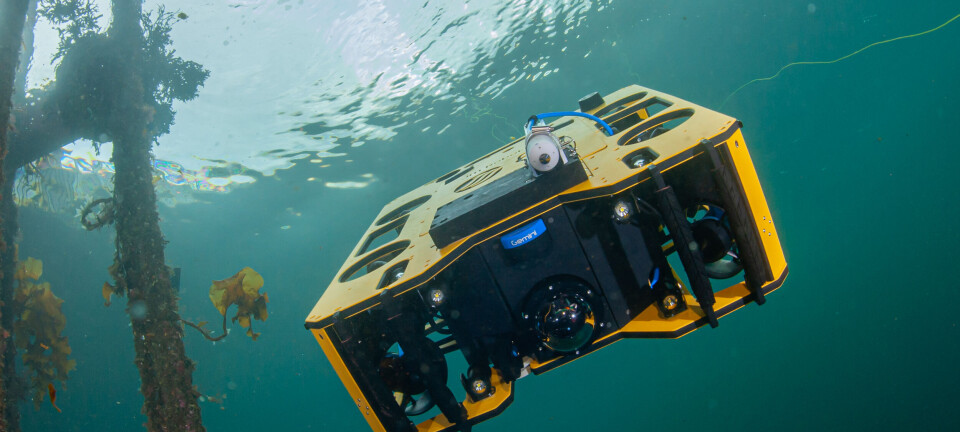

Part of why the harmful algae bloom (HAB) has caused such a problem is that it extends 25 metres down into the water-column, making it impossible for the farms to deploy their usual mitigation methods.

"We would put down tarps around the outside of the farm, and then we would pump water up from below the bloom, but unfortunately in this case the bloom is so deep, it's deeper than the pens, so there's not a whole lot we can do," said Grant Warkentin, spokesperson for Cermaq.

“Such a large bloom of this type of algae is unusual, and something we have not experienced before”, said Cermaq. “We are removing the mortalities daily and are continuing to monitor the situation at this time.”

The typical species of algae for this time of year are Heterosigma and Chatoseros spp., so this large bloom of Chrysochromulina was an unusual occurrence, according to Cermaq.

However, this event, although significant, pales in comparison to the algae bloom that just ravaged the Chilean coast, resulting in millions in losses as over 100,000 tonnes of Atlantic salmon, coho salmon and rainbow trout were killed by a massive HAB.

Rubbished by research

A research study conducted in 2012 by scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and published in the journal Harmful Algae, concluded there is little evidence to support anthropogenic factors as the cause of algal blooms in most areas along the Pacific West Coast.

They found that blooms are strongest in the drier seasons, usually start offshore and move onshore when upwelling winds relent.

“Although some blooms start nearshore in BC and WA, in general blooms occur during periods of warmer surface temperatures, which characterize periods of stratification in upwelling regions. Thus, these [paralytic shellfish poisoning] events appear related more to large-scale oceanographic forcing,” the authors concluded.

Interestingly, the study found that in places devoid of human activity, including aquaculture, algae blooms are common.

“Alaska has a long history of encounters [with HABs] that occur along much of the Gulf of Alaska coast from the BC border in the southeast to the Aleutian chain and into the Bering Sea on the west and more northerly coasts…There is no evidence to support anthropogenic factors as promoters of [harmful algal] blooms or toxic events in this region. The shoreline is long and complex, human populations are remote and widely disbursed, and there are many streams, rivers, islands, and extreme weather events that produce a complex marine ecosystem.”